By Hannah Wilson, Curator

World War II presented new challenges to policing - air raid precautions, ration fraud and captured enemies all needed to be dealt with, on top of the usual crimes. Additionally, 291 officers left the Force to serve in the Armed Forces during World War II. Many new roles were created to meet the demand for man power, and children as young as 15 were recruited as messengers. In total 32 officers from the Essex, Colchester and Southend forces were killed on military service. A further 2 were killed in the HQ bombing and many more suffered personal losses.

This article is split into five sections: Roles and Responsibilities, Headquarters, Personal Stories, V.E. Day and From The Collection.

Section One: Roles and Responsibilities

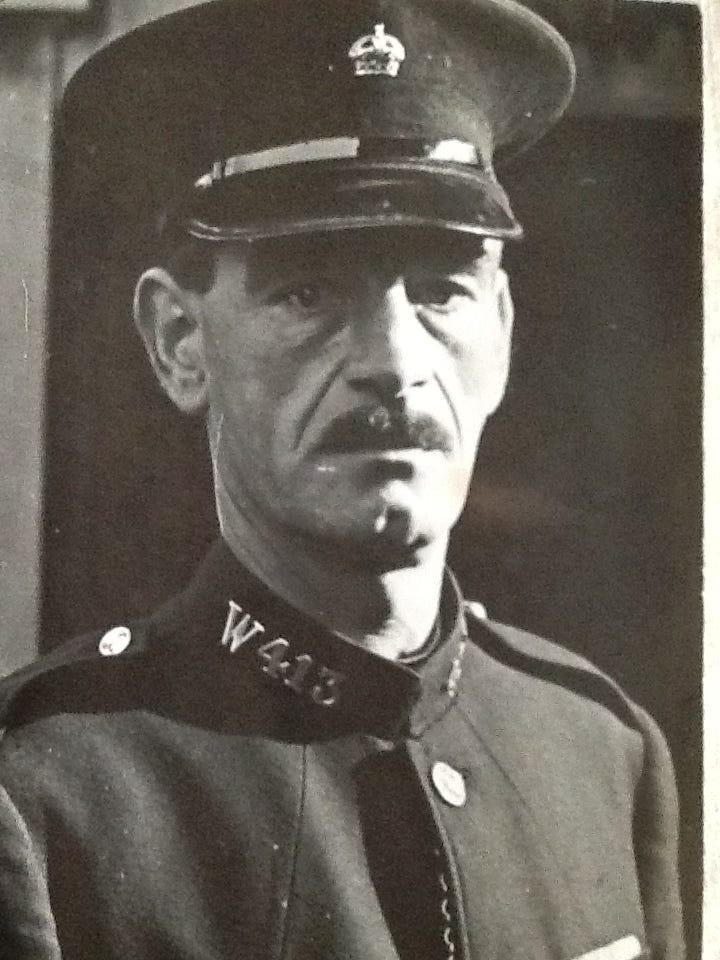

Special Constables

Special Constables were invaluable throughout World War I, providing much needed assistance and man power. When the Home Office disbanded Special Constabularies after the war, our then Chief Constable, Captain Showers, opted to create the Essex Police Special Constabulary Reserve to keep the Specials ‘on the books’. When the Second World War broke out two decades later Essex was much better prepared - protocols and procedures for recruitment, training and distribution were already in place. In total, 272 Special Constables were recruited for full-time duties.

First Police Reserve

In addition to Special Constables, Essex Police created several other roles to protect the County. One of the more obvious ways to boost police numbers was to recruit retired officers - they were familiar with the County, familiar with the role and likely had some lived experience of World War I. During covid a similar system was used within the NHS, with retired doctors and nurses returning to provide man power. It is likely that due to their age and experience, the First Police Reserve had some input with training new recruits and conducting air raid patrol lectures.

The War Reserve Police

Not to be confused with the First Police Reserve! War Reserves were temporary police officers who joined for the duration of the war. They rarely had any previous police experience and there was no rank structure: all were Constables. All war reserves had a record of service, as did Specials and new regular Officers. That being said, there are some gaps in our collection around both World Wars, owing to the additional demands on admin personnel, bombings and relocation of records.

The Police Auxiliary Messenger Service (PAMS)

The youth also aided police during World War II. A group of 211 part-time volunteers aged between 15 and 18 formed the Police Auxiliary Messenger Service (PAMS). They acted as messengers, using their bicycles to deliver messages throughout the War.

Andrew Harvey from Thorpe-le-Soken remembers:

‘…The idea was to take messages from Thorpe-le-Soken to other police stations and bring messages back. We wore an ordinary police blue steel helmet with P.A.M.S on the front and we were issued with a service gas mask and a pin badge.’

The Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps (WAPCs)

The Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps (WAPCs) did office or switchboard work, and sometimes street patrols, although they had no police powers. Their uniform was based on that of male officers, but had some changes: their hats were unique, they had skirts instead of trousers and their tunics were belted.

Training and Additional Responsibilities

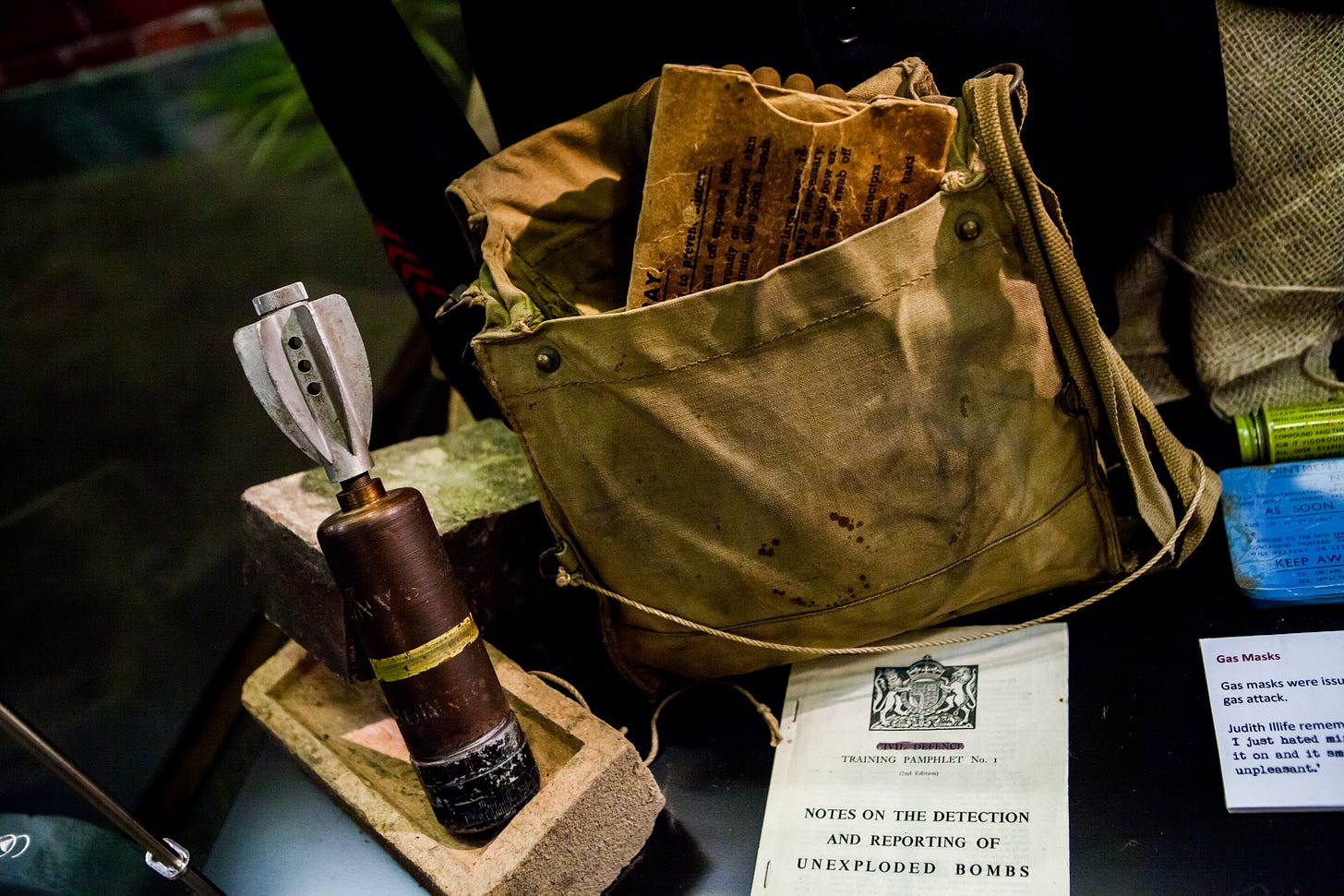

The new roles were needed - officers had a massive increase in their day-to-day duties and were trained to deal with everything war could bring. Officers were expected to attend unexploded bombs and cordon off the site, evacuate members of the public and personnel, guard crashed aircraft and recover their crews, capture enemies, search for survivors in bomb-damaged areas, maintain air raid sirens, police the black-out, give lectures on air raid precautions and anti-gas measures, and enrol air raid wardens and volunteers for the Home Guard. All of this, of course, was in addition to their usual police duties.

In 1941 a training school was opened at Headquarters to give basic training in police duties, civil defence and first aid to over 600 auxiliaries from Essex and elsewhere in the country.

A Downed Aircraft At Chelmsford

Police officers faced challenges and an increased risk of danger on every shift. One such challenge was responding to a downed German aircraft at Baddow Court in Chelmsford.

Officers responding had very basic equipment: A gas mask, a metal hat for protection, a lamp, a rattle, and either a whistle or a hand bell to draw attention. There was very little radio communication and no digital equipment.

An Unfortunate Accident

It wasn't just enemy bombs that the nation had to worry about. Training exercises sometimes used live explosives and this carried significant risk. In Gestingthorpe in 1943 an instructor accidentally detonated a missile whilst instructing members of the Home Guard. The blast caused a number of mortars and bombs to explode, killing all present. The images show the aftermath of the blast.

Section Two: Headquarters

A Key Target

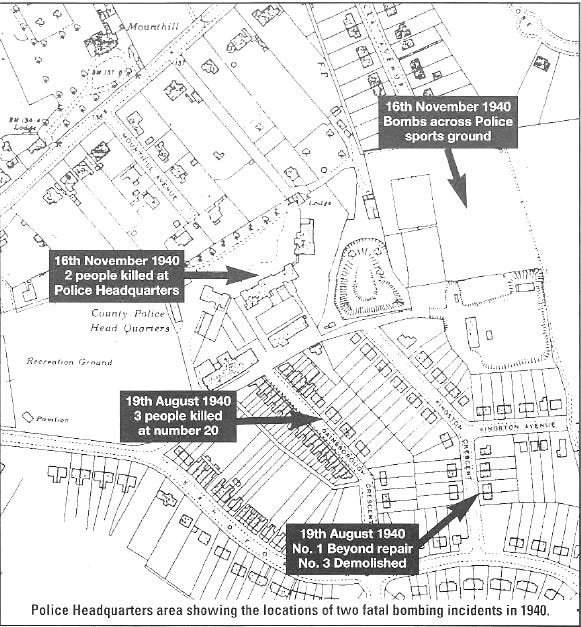

Essex’s coastline, proximity to mainland Europe and proximity to London put the County at a higher risk for invasion. If the enemy could disrupt the police force, invasion would be easier. As a result, the Headquarters in Springfield, Chelmsford was a target for air raids and enemy action. Unfortunately, this meant the surrounding housing estate, which were mostly police houses at the time, were also affected. Several suffered direct hits or extensive damage, and in some cases houses were completely destroyed. This house was bombed in September 1940 and was rendered inhabitable.

This was just one of the many worries faced by police officers and the general population at the time. Some police houses had air raid shelters, and public shelters were within range of the Headquarters estate. That being said, there are multiple accounts of residents having little to no notice for some air raids. In one account, a child recalled hiding behind a garden wall on the way to school as there wasn’t enough time to get to a shelter.

Jack Palmer, Air Raid Warden, reflects:

"The first bombing incident I can remember once I’d become a warden was one weekend in November 1940 when my brother-in-law came down to visit us from Hanwell. He was also a warden so that particular evening he offered to come out with me on my round during an air raid alert. As we were out in Springfield Park Road a German bomber suddenly appeared overhead and dropped a stick of about sixteen small bombs.

As soon as we heard them whistle we dived to the ground for cover. I remember my brother-in-law frantically searching his pockets for a rubber he carried with him – you were supposed to put it between your teeth so that even if you were knocked out by the blast or whatever you’d still be able to breathe! The bombs fell outside our sector, across the Police Headquarters, where two policemen were killed, and into the fields nearby. It was a shock to my brother-in-law who had never heard so many bombs go off so quickly after one another. “Blimey!” he said, “we don’t have ‘em drop like that in London!”. After the plane went we got up off the ground and continued our round."

A Direct Hit

One evening in November 1940, a German aircraft released bombs across Springfield, hitting Headquarters. The first bomb landed in front of the main entrance and two officers, PC Alexander Scott (aged 26) and Detective Maurice Lee (aged 27) were killed.

The building was protected by sandbags, saving it from any major structural damage, but there was extensive damage to the roof, windows and ceilings throughout. An early assessment reported that not a single window remained whole and the clock had stopped at 7.17pm, the exact time of the blast.

The second bomb landed in the Chief Constable’s garden opposite the room where Captain Peel and his wife were eating dinner. Fortunately they escaped serious injury, although the house was badly damaged.

During the clean up numerous pieces of shrapnel and other debris was collected and displayed on the lawn at HQ. The display shows the range of devices dropped in the area, including an array of smaller incendiary bombs and larger bombs with parachutes.

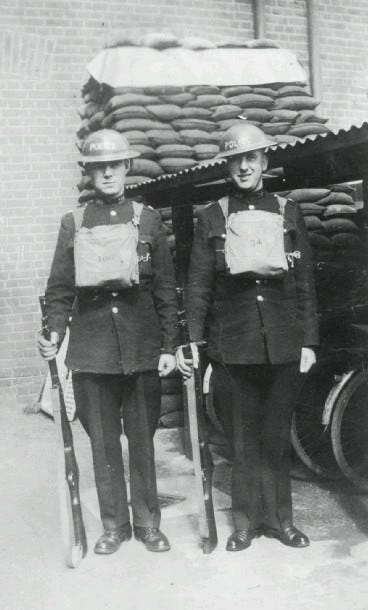

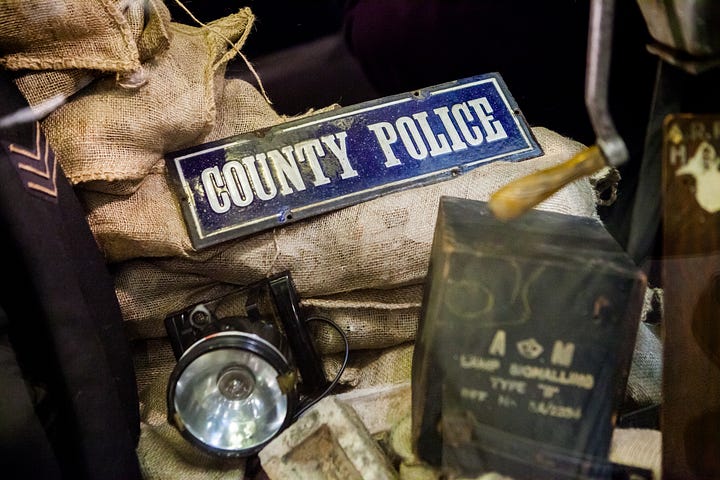

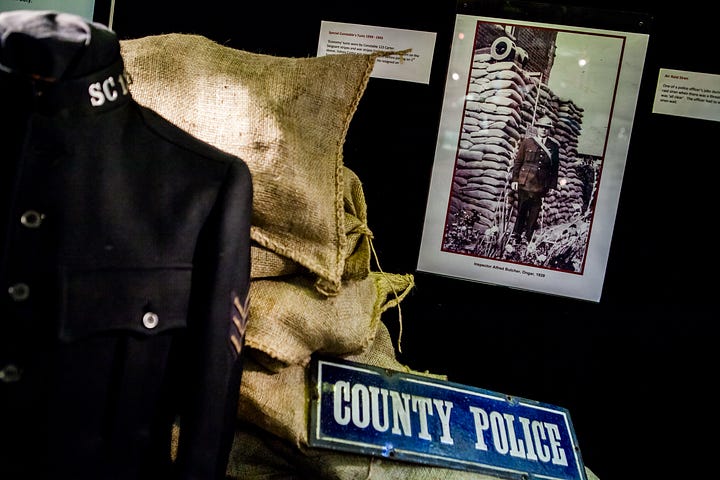

Other Police Buildings

Many police buildings were sandbagged to protect against bomb damage. In the case of the old Southend Police Station in Alexandria Street, shown below, sandbags were stacked as high as the first floor! Police buildings were also subject to blackout regulations, and this combined with the sandbagging and other precautions caused stuffy and unpleasant conditions.

Section Three: Personal Stories

Inspector Harold Tomalin

Inspector Harold Tomalin wrote a letter describing his experience as an officer in World War II, shown below.

Transcription:

“Inspector Tomalin At Work

Throughout the War I had to report, in addition to ordinary duties, for fire-watching or any other emergency which might arise owing to enemy action.

For many months I had to report on each occasion the siren sounded, and remain until the area was known to be clear and under police control. This occurred so frequently that a system had to be devised, whereby I reported from blackout until 7 o'clock the following morning on alternate nights.

Towards the end of 1944 it was again reorganised whereby it was only necessary to report every 4th night.

Whilst off duty fire watching, we usually sat up late in case of emergency duty and then slept rough, fully clothed on camp beds, in small rooms with other men. These rooms could not be properly ventilated owing to the blackout panels on the inside and blast walls on the outside of the windows.”

The letter paints a clear picture of the extent to which World War II impacted officers on duty. They had to be ready 24/7, sometimes staying away from their families, and many took to sleeping in their uniforms to save precious minutes when they were eventually able to get their head down. For both officers and civilians the constant threat of danger and waiting for air raids was exhausting.

Judith Tomalin

Judith Tomalin, daughter of Harold Tomalin above, lived at 31 Kingston Crescent during the war. Although a young child at the time she remembers being frightened by the air raids:

"If the siren had gone and we knew there was going to be an air raid you did feel frightened because the sirens only went when there was danger of some kind. Some of the bombs that were dropped were called incendiary bombs and they were mostly used at night time. And they I think lit up the whole area and some of the women used to be on fire watching duties and probably some of the older civilians. And they would warn everybody that there were fires using a rattle – like a football rattle and blowing whistles and making sure that people knew there was danger. They were the incendiary bombs.

Then there was another set of bombs that we used to call doodlebugs and I think they were the ones, you could hear them whistling, and they would suddenly stop and there would be this dreadful silence and you’d wonder ‘I hope it’s not going to drop on my house or near us.’ And of course the last ones towards the end of the war were big rockets that were sent over. They didn’t have far to travel and I understand they were sent from rocket launching pads from the channel which isn’t far as the crow flies or as the rocket flies! And so we did dread those very much."

31 Kingston Crescent is now private property, but before it was sold it was our museum store. The old air raid shelter still stood in the back garden although it had been filled with rubble and was a little worse for wear. In 2006 museum volunteers cleared the space to get photos of this important part of HQ history.

Judith tells us it was unpleasant right from the start:

"The walls were ever so smooth and the whole place smelt of wet concrete. I think that’s why we didn’t really use it very much. I did sleep down there a couple of times – but I didn’t like it. Several families had bonded together – I think to pay for it but it was all done with permission, you didn’t suddenly construct something like that on police property."

The Civilian Experience

It wasn't just police houses and buildings that suffered extensive damage. This first-hand account from an officer in Southend* shows the challenges faced by ordinary people:

*At this time Southend had its own police force, entirely separate from Essex County Constabulary. You can find out more about Borough Forces in our history notebook no.53.

“Southend County Borough Police

Date: 22nd April, 1941

Enquiry RE: Incendiary Bombs Extinguished

Sir

I beg to report that about 11.15pm on Saturday, 19th April, 1941 a number of incendiary bombs were dropped in the gardens between Marine Ave and Westleigh Ave. I was successful in smothering three when the landmine exploded and I was blown across some gardens. A fire then broke out in the rear rooms of a house in Westleigh Ave occupied by [omitted]. With the help of Mr [omitted], the Buildings Inspector, I was able to extinguish the fire which was caused by an electric fire overturning and igniting the floor and furniture. I then searched the debris of [omitted] Marine Avenue [and rescued] Miss [omitted] from under the table. She was uninjured. I then reported at Leigh Police Station and remained there until the Raiders Passed signal and reported off duty at 4.55am 20/4/41.”

In a follow up report, the Officer writes of the same incident:

“Southend County Borough Police

Date: 23rd April, 1941

Enquiry RE: Attached Report

Sir

I beg to report with further reference to the attached report. In the first instance I knew that Miss [omitted] was under the table because at about 10 p.m. I went over to her premises and asked her if she would care to come over along with us as the gun fire was heavy. She declined my offer but stated that should anything happen she was making herself comfortable under the table in the dining room. This table is a very large heavy one and very substantial. Her premises [omitted] was in immediate passage of the blast. The whole of the back was blown in. The tiled roof and doors blown in. The furniture which comprised of a heavy book case, sideboard, piano chairs etc were all blown to the front and covered the table which Miss [omitted] was under. The ceiling was of Essex Board was down and covered this as was also a great number of the tiles. With the help of Mr [omitted] I forced a passage into this room in which Miss [omitted] was in through the furniture etc and found Miss [omitted] under the table amid broken glass, potware, books etc cuddling her canary. I then took her over to my house and later to [another property] where she is at present stopping. Her house is a total wreck and it is feared that the upper floors are liable to collapse at any time. Fortunately Miss [omitted] is uninjured. Had I not known where she was in the house it is possible she would not have been found till daylight next morning.”

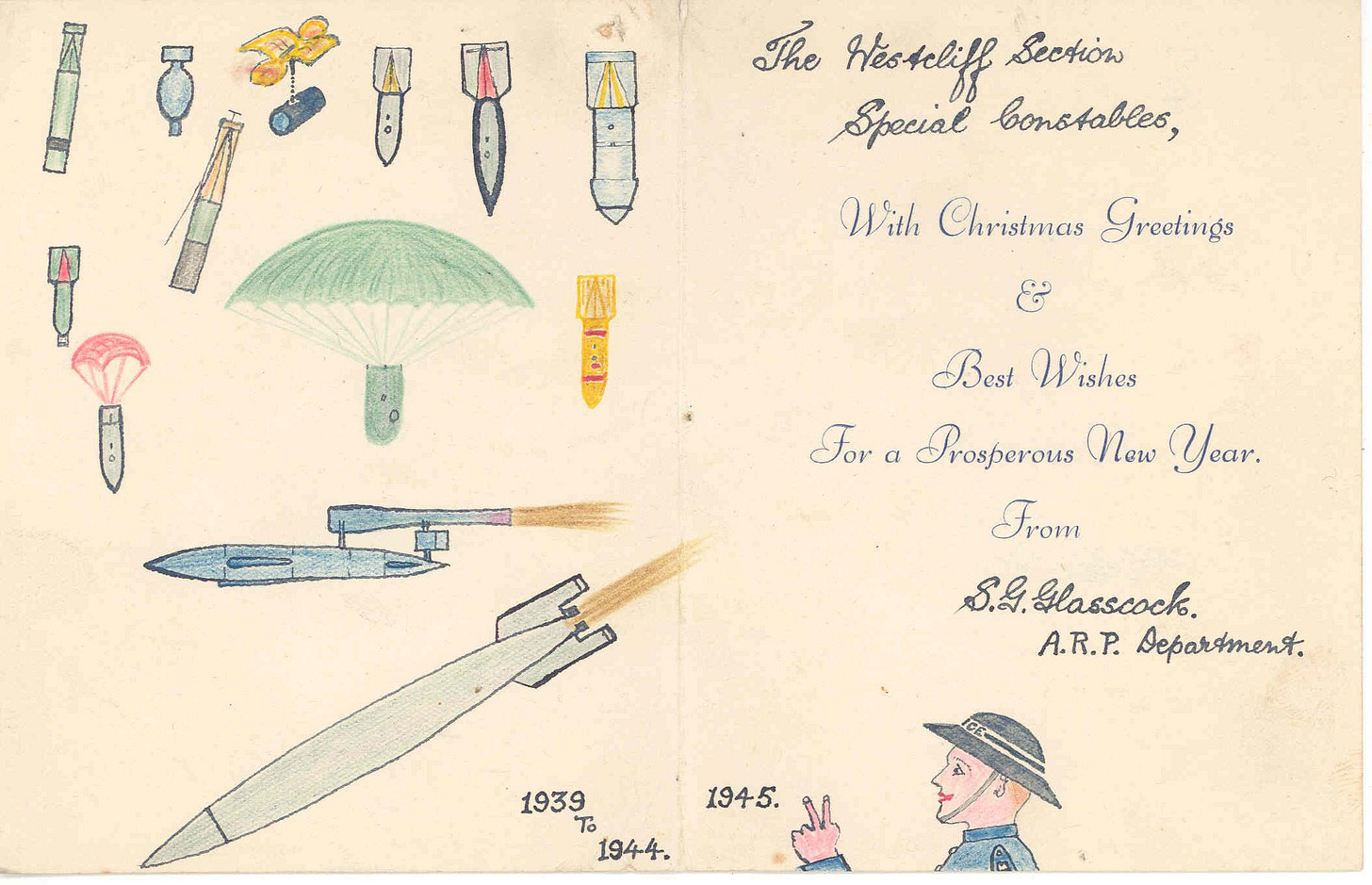

Civilians were grateful for police assistance and there was great comradery between all involved in the war effort. This Christmas card was given to the Westcliff Special Constables from a Southend Air Raid Patrol Warden. It has been hand-illustrated with the various explosive devices seen in the area. You may recognise some of them from the display on the HQ lawn in the Headquarters section of this article.

A Child’s Story

It wasn't just adults who had to deal with the bombings. In this eyewitness account, gathered in 1997, Gordon Oakley reflects on the day his house was destroyed. He was just 11 at the time, remarkably surviving the direct hit.

"It was lunchtime on a clear summer's day and I was at home sat around the table in our front dining room with my sister, mother, aunt and cousin, having just finished our meal. Then we heard, a droning noise which I'd come to recognise as a German aeroplane. As a typical eleven-year-old, I'd become fairly expert at distinguishing our aircraft from the Germans by studying aircraft silhouettes and so on.

I rushed over to the bay window at the front of the house to see outside and as I looked, up I could see a German aircraft coming from the direction of police headquarters. I shouted a warning to the family, something like 'It's one of their's!'. That is the last thing I can remember until I came round, actually, under the table - how I got blown backwards from the window towards the bomb there is no telling! I never heard the sound of the bomb dropping, or even the house falling down. You can't really say that I was trapped, because I was able to pull away various bits and pieces of debris and crawl out to daylight.

There I found that our house had been totally destroyed and was reduced to a pile of rubble. Remarkably Constable Shepheard’s house next door was still intact, and apparently a newspaper reported that it didn’t even have a broken pane of glass. The fireplace which backed onto his house was still there and I saw my cousin standing right beside it with her hands over her face. I got hold of her and we scrambled across the rubble to the road. Fortunately neither of us was injured – I didn’t even have a cut even after clambering out over all the bricks and rubble.

The next thing I knew there were people shouting – a crowd of policemen had come out of headquarters and rushed down the road to start searching the debris for survivors. They took charge and one of them got hold of my cousin and I and took us a few doors down the road, I think to number 8, where someone invited us in and gave us comfort. My dad who had been in the kitchen getting ready to go on duty, had survived the bomb, and he stayed at our house to help with the rescue efforts.

A short while later there was an enormous panic when they discovered that some of the string of bombs had landed in Kingston Crescent, but had not gone off. That meant that we had to evacuate the area so they brought a police car down from headquarters and I was put in it and taken off to relatives of my father in Brentwood. My cousin was taken back to her family up Ipswich way. Of course I had nothing, no clothes nothing at all, so after a couple of days I was taken out shopping in Brentwood. While we were out another German bomber came over. As I watched it dropped bombs which I thought had fallen on where I was now living, but fortunately it turned out to be the next street.

It was at Brentwood that my dad told me that my mother, sister and aunt had all been killed. My mother and sister had been sitting nearest to the door to the hallway and were both dead when they were dug out. Apparently my aunt had left the dining room to go to the kitchen to warn dad when the bomb exploded near the hall. She stopped all the shrapnel in her back which presumably saved dad. She was rescued alive and as she was being carried out on a stretcher she asked someone to wish me aunt, Geri Totterdell, a happy birthday. Although she was still conscious at that stage she died later in hospital.

My father had previously been stationed at Rettendon and through that he was able to get hold of fruit that my sister and I used to weigh up and sell from our house, making a bit of pocket money for ourselves. We used to keep the money in a bakerlite bowl on the mantle piece and I remember seeing that intact when I got out from under the table. However, once the site was cleared afterwards the money and bowl went missing – that has always griped me.

After the bombing I went back a few times to Gainsborough Crescent to see the site after it was cleared and I watched the house being rebuilt, but I never lived there again. I followed my father into the police and since retiring I frequently visit headquarters to attend functions, parking in Gainsborough Crescent. Then I often stop outside my old house and reflect on the bombing.”

Christmas During Wartime

Despite the disruptions, loss and damage it wasn't all doom and gloom during the war years. The war brought the whole community together and holiday events carried on as best they could. These images show a Christmas Party held at the Essex Constabulary's gym in 1942. All local police families got together to celebrate. Rather unusually, compared to the general population, many men stayed with their families instead of going off to war as police work was a protected occupation.

Section Four: V.E. Day

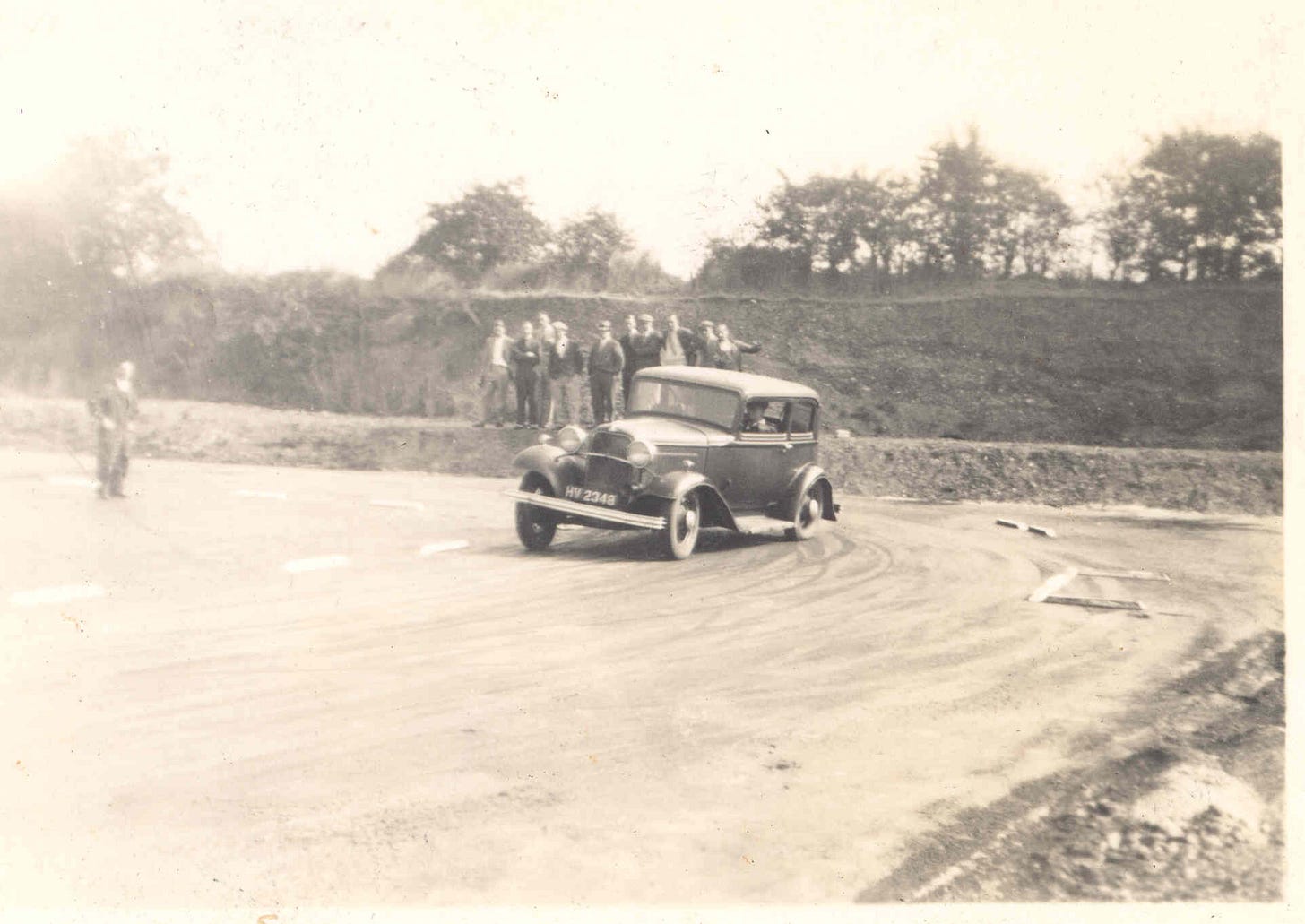

The skid pan was used to train officers to drive safely in dangerous and slippery conditions, and in World War II was repurposed for air raid precautions training. When the victory in Europe was announced the skid pan was repurposed again - this time the whole HQ community came together to create a huge bonfire on it to celebrate!

The V.E. Day celebrations were some of the happiest memories for local children. Judith Tomalin remembers:

"Well that was a very happy time...on V.E. night there was a huge bonfire put in the middle of the skid pan and we all went down to it. Instead of Guy Fawkes on the top Hitler was on the top and as you had walked down to the skid pan there was a huge hut, an army hut, where all the police stores were kept and from the roof of that on a wire they let down a huge model, I think it must have been something that the Luftwaffe used to fly over here and I can’t remember the name of the plane but anyway it came down in flames into the bonfire and it was a very happy occasion!"

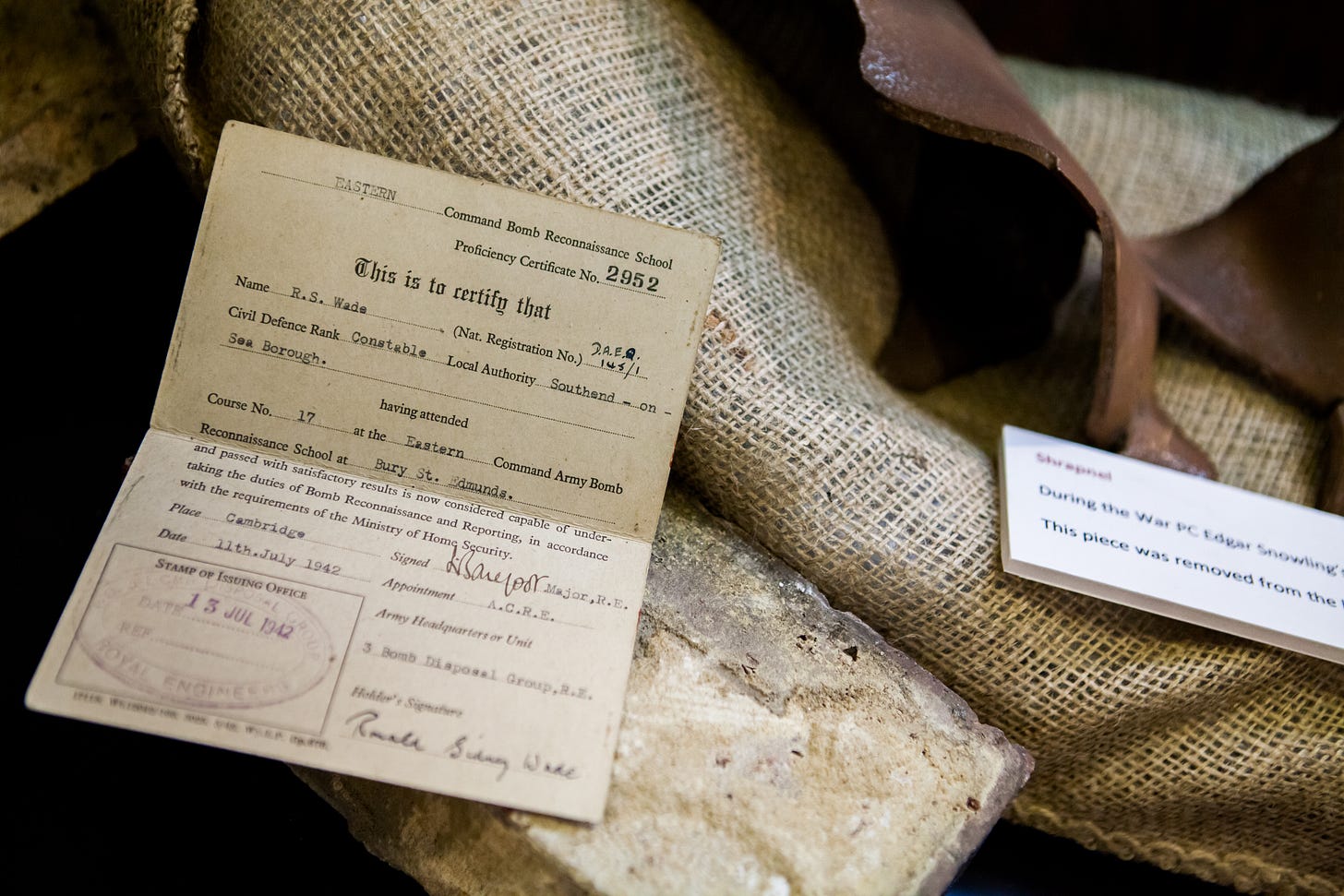

Section Five: From The Collection

These images and objects dating from World War II offer a glimpse into everyday life and the challenges faced by both Officers and civilians.

We Remember

Today we remember the fallen with a memorial stone, flanked by 2 trees to represent the Essex County Constabulary, Colchester and Southend Boroughs respectively. Boards listing the names of each fallen officer are also displayed in HQ reception. Every year on remembrance day everyone present at HQ gather by the stone for a short memorial service and a moment of silence in respect.