HN 1. The Murder of Sergeant Eves

“One of the worst murders which ever disgraced this country”

By Martyn Lockwood, retired Inspector and Honorary Member of the Essex Police Museum Committee.

Content Warning: Mentions the death penalty (hanging) and contains descriptions of a violent murder.

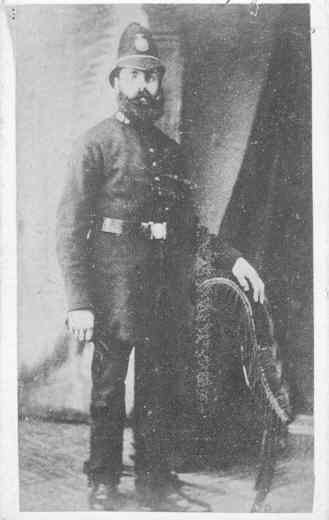

Adam John Eves, a native of Hutton, near Brentwood, joined the Essex Country Constabulary at the age of 20 years, and in March 1877 was appointed Constable No. 63. He served at various stations throughout the country before being promoted to the rank of Acting Sergeant and posted to Purleigh in January 1891. By April 1893 he was dead, murdered whilst carrying out his duties.

Eves was a wheelwright by occupation before joining the police. Like other constables who joined at this time, he entered upon a career and embarked on a way of life that demanded almost unremitting hard work performed under conditions of severe hardship. Assaults on constables were common and in the course of their duty they were expected to walk upwards of 20 miles day. Meal breaks were uncommon, officers were expected to eat on duty; and it was not until 1910 that they were granted a weekly rest day. In exchange a constable received a weekly wage that left him, and especially the married man with a family to support, near to the breadline. Wages were no better than those offered to agricultural labourers. On joining, Eves, as a Constable (3rd class), received a salary of 21s (£1.10) per week.

Discipline was strict and punishment imposed arbitrarily. The Chief Constable was the sole disciplinary authority, with power to fine, reduce in rank or class, or dismiss any officer who appeared before him with a breach of discipline.

Eves, who was married in 1878, lived with his wife Elizabeth in a cottage at Purleigh. He was a popular officer in the district, who could be relied upon to discharge his duties diligently. However, in the course of his work he had made a number of enemies amongst the criminal classes and had been threatened on more than one occasion with violence.

On the evening of Saturday, April 15th 1893, Eves set out on his usual patrol of the district. About 10pm he called in at the Royal Oak public house, where he spoke to the landlord and handed him a reward notice concerning the poisoning of rooks in the district. Due off duty at midnight, his wife was not unduly alarmed when he failed to return and she went to bed. When she awoke the next morning and found he had not returned, she comforted herself with the thought that he had been detained by a fire in the district. However, as the day progressed she became more and more alarmed by his absence. About 2.30pm that afternoon Herbert Patten, a local carpenter who she knew, walked past her cottage with his girlfriend. Mrs Eves asked Patten if he had any knowledge of a fire in the district. He told her that he had not heard of any fire, whereupon she became further concerned and said “You never know whether they’re going to be brought home dead or alive.”

Puzzled by the remark, Patten and his girlfriend continued on their walk across the fields at Hazeleigh Hall Farm, which lay about a mile from Purleigh. As they approached a spot known locally as Bellrope Gate, he noticed signs that the ground had been disturbed and looking down he saw to his alarm that the grass was saturated with blood. Nervously he looked into the deep ditch nearby and recoiled in horror as he saw the body of Adam Eves lying in the body of the ditch in six inches of water. Eves had suffered dreadful injuries, the body was terribly mutilated and his throat had been slashed from ear to ear.

Patten ran for help to Stow Maries where the nearest constable lived. He told the astonished Constable Chaplin of his discovery and the two men hurried back to the scene of the murder. On their way they came across Inspector Pryke who was in the area making enquiries into the theft of corn from a barn at Hazeleigh Hall Farm during the night. The Inspector and PC Chaplin examined the mutilated body of Sergeant Eves. They noticed that his truncheon was still in his pocket and the shutter on his bulls-eye lamp was in the ‘off’ position. As they moved the body they found three stout sticks lying underneath. One stick was broken into three pieces and all were soaked in blood. A search nearby revealed a bloodstained spade and three corn sacks lying nearby. A trail of spilled corn led towards Bell Rope Gate. The two officers also noticed a set of wheel marks in the grass leading from the scene to a group of nearby cottages.

The body of the dead officer was moved to his home. Superintendent Halsey telegraphed the Chief Constable with the news of the murder and Captain Showers sent two officers, Inspector Terry and Detective Sergeant Dale, to Purleigh to assist with the enquiries. They set up their headquarters at the Bell Inn. Initial enquiries revealed that several threats had been made against the dead officer and only a short time before his death he told a villager that one man had said, “If I ever get the chance at you, I’ll take you.” Suspicion at an early stage fell on a group of men from the village, all petty criminals with bad reputations. In July 1891 Eves had been assaulted by one of these men, John Davis, whom he had arrested for poaching. For this assault Davis received 2 months imprisonment with hard labour.

Inspector Pryke was dealing with a theft of corn which had occurred at Hazeleigh Hall Farm. It had been reported on the Sunday morning to the police by the son of the farm bailiff, Joseph Moss, who had discovered that attempts had been made to force the door on the granary. Pryke’s enquiries into the theft showed that false entries had been made in the farm ledger and a greater quantity of corn had been stored in the barn that was shown. Edward Fitch, the owner of the farm, estimated some 13 bushels of corn were missing. The police now had a possible motive for the murder. Had Eves come across the men as they carried the corn away from the farm, tried to arrest them, then been killed in such a violent manner?

The Essex Constabulary acted swiftly, and on the Monday morning Inspector Terry and Sergeant Dale visited the house of John Davis, a labourer aged 34 years. There was no one at home so they called at the home of his brother, Richard, aged 30 years, also a labourer. Outside the house they noticed a hand cart. Looking into it they saw stains which appeared to be blood. Both brothers were arrested. PC Chaplin made a search of a pond in Richard Davis’ garden and recovered three sacks of corn. This corn and that found scattered at the scene was similar to that stored in the barn.

Other arrests took place that day. Charles Sales, a dealer aged 47 years and John Bateman aged 37 years, were arrested by Superintendent Halsey and Inspector Pryke. All four were local men, well known in the locality and each had previous convictions for theft and poaching. They had worked together in the past and had recently been engaged in threshing corn at Hazeleigh Hall Farm. When Sales was arrested, bloodstains were found on his waistcoat, caused he said, by a bone he had bought. The blood in John Davis’ cart (he told police) had been caused by a sheep’s head which he had bought in Maldon on Saturday. Blood was found on the back of Richard Davis’ coat and shoes. Bateman’s clothes were stained - he explained this had been caused by porter from the public house. When interviewed Bateman admitted to the police that he had been lying out all night in the very field Eves was murdered. All four men were remanded in custody and conveyed to Chelmsford Prison for a week.

On the Wednesday morning a villager, Thomas Choat, went to the police and made a statement concerning a Hames Ramsey and his son John. Ramsey had been the driver of the threshing machine at Hazeleigh Hall Farm, his son the chaff boy and Choat had been the feeder for the threshing machine. He told police he had heard James Ramsey make threats against Eves and on the Monday after the murder Ramsey had turned up for work wearing new clothes. Ramsay and his son were arrested and taken to Maldon Police Station. A search of their home revealed a pair of blood soaked trousers and Choat told the police that James Ramsey had worn them on the Saturday. Sacks similar to those used to steal wheat were found concealed under his mattress. They too were remanded until the Monday.

On the 24 May 1893, John and Richard Davis, Charles Sales and James Ramsey were committed for trial at the next Essex Assize. The case against John Bateman and John Ramsey was dropped because of insufficient evidence. In the witness box Bateman told the Magistrates that Sales had admitted his guilt and had implicated both the Davis brothers. The Magistrates ruled his evidence inadmissible as neither Davis was in court to repudiate his statement.

The trial commenced at the Assize Court at Chelmsford on the 3 August 1893 before Mr Justice Mathew. All four prisoners pleaded not guilty to the charge that they had murdered Sergeant Eves. Mr Crump QC opened for the prosecution and outlined the case to the hushed court, which was that the four men had been involved in the theft of corn from Hazeleigh Hall Farm where they worked. Eves, on his way home that fateful night, had come across the men making their way from the farm with sacks of stolen wheat. He had challenged them and they set about him and murdered him, throwing his body into the ditch where it was found by Patten. Evidence of the cart tracks was introduced. Ownership of the cart was never disputed by Richard Davis and he had told police he had used it to collect stones from the very field where the murder took place. The spade found at the scene near the body was identified as belonging to him.

On the second day of the trial the case against Sale was dismissed and he was discharged. The defence called no witnesses. Ramsey and the Davis brothers maintained their innocence claiming they were in bed asleep on the night of the murder. Their only case was that other men worked at the farm and had the opportunity to steal the corn, inferring that the evidence produced by the prosecution was purely circumstantial. In his summing up Mr Justice Mathew told the jury that the theft had been planned. The tally at the farm had been altered and those who had stolen the corn had murdered Eves. The jury retired at 3.26pm and returned at 4.46pm. In little over an hour and a quarter they found the two brothers “guilty” but James Ramsey “not guilty”. The judge donned the black cap and amid the deafening silence of the courtroom he pronounced sentence of death, telling them both not to hold out any hope of a pardon in this world. “From the Almighty, as I hope you know with penitence and contrition you will obtain forgiveness for your most grievous sin.”

Richard Davis lodged an appeal against his decision. His brother John, resigned to his fate, confessed to the murder. He said that all three men had been involved in the theft of the corn. As they were carrying it home they had been surprised by Eves, who grabbed hold of him. As they struggled on the ground Ramsey came up and struck a number of blows to Eves’ head with his cudgel. His brother Richard had played no part in the assault and, as the unconscious officer lay on the ground, Ramsey cut his throat with a knife. The three of them then threw the body in the ditch. Richard Davis was later reprieved and sentenced to imprisonment for life. John Davis paid the ultimate penalty by being hanged at Chelmsford Gaol on August 16th 1893. The story might have ended there, but for the arrest of James Ramsey, charged with breaking and entering the barn at Hazeleigh Hall Farm, and stealing thirteen and a half bushels of corn. He was brought before Chelmsford Assizes in November 1893 to be tried by Lord Chief Justice Coleridge.

Selina, the wife of the late John Davis, had been prevented from giving evidence at the trail of her husband. She now told the court that about 9pm on the night of the murder she was at home and was about to go to bed, when she heard a knock at the door. James Ramsey entered carrying a bundle of sacks. She left her husband talking to him but heard them leave the house about an hour later. Richard Davis was brought from prison to give evidence. He told the court that on the night in question he was asleep at his cottage when he heard a knock at the window. Looking out he saw his brother John. He got dressed and went to his brother’s cottage where he found him with James Ramsey. John Davis had two bundles of sacks and Ramsey had one. They all left the house, the two men told Richard that they were going to Hazeleigh Hall Farm to steal some of the wheat they had been threshing. They went to the barn, and having had some difficulty forcing the door, eventually crawled into the barn. They set about the task of filling their sacks. Three sacks were taken outside and hidden in a gap in the hedge whilst the three took a further sack each and made their way to their homes.

The court was hushed as Davis continued. The three men were walking across the field. Richard led, followed by John with Ramsey bringing up the rear. Suddenly Richard heard his brother call out to him and heard the sound of a scuffle in the darkness. He turned to see his brother, Ramsey and Sergeant Eves rolling about on the ground. Davis was asked, “What condition was the police sergeant in?”, Davis replied, “He was quite dead.”

He then told the court that he had taken no part in the fight and was abused later by Ramsey for not coming to their assistance. John told him later that he had struck Eves with his stick and that Ramsey had cut his throat. The three men then decided to throw the body into the ditch where it was found. They hid the three sacks of corn they had with them in the nearby pond. Their clothes were bloodstained and Ramsey said he would burn his when he got home.

Davis was cross examined by Ramsey. Ramsey accused the two brothers of the murder. That man was not killed in a minute. You and your brother knocked him about and left him for dead. I never touched him. You went home and got a spade to bury him. When you returned he was still alive. You knocked him about till his poor head was in pieces.” Davis replied, “You did it, and no one else. You put him in the ditch.”

In his summing up His Lordship told the jury that from Ramsey’s description of the crime he had been at the spot himself, and stood guilty of his own confession. The Jury found Ramsey guilty without leaving the box. He was sentenced to 14 years penal servitude. In his address to the prisoner His Lordship said, “I should ill discharge my duty if I shortened by one single hour the sentence which may be passed on you.”

The funeral of Sergeant Eves took place at Purleigh a week after the murder. The cortege was led by the Chief Constable and over 150 members of the force attended. Eves was held in such high esteem in the neighbourhood that the route to the church was thronged by grieving villagers. Mrs Eves was awarded the maximum pension payable at that time, £15 per year, and a public subscription raised £400. She continued to live in the village.

A Postscript

As the years went by the fine new headstone fell into decay and memories of the event grew dim. That it was a fearsome crime was the opinion of the earliest issues of “Police Review and Parade gossip” first published in that same year of 1893. This was the first murder of a policeman that it covered.

The writers described the scene as the officer, alone in a field and miles from his nearest colleague, fought his last battle. It was not the kind of battle with flags and bands, where the enemy could be seen and medals anticipated, but a more primeval and savage kind, which took place in a pitch blackness, where all that could be heard were the grunts of the antagonists and the thud of thick sticks on flesh.

The traditions of the constabulary still exist, though the title had changed. A constable called Graham patrolled that same area. It is still pretty lonely at night, but duty to the people of Essex is still recognised and sought after by modern policemen. By his own effort he has ensured that the grave of Acting Sergeant Eves has been restored and respected. Essex Police will also try to ensure a supply of their men and women who are trained and motivated to put themselves at risk on behalf of the community in much the same way as that lonely figure a century ago.