HN 10. The Sible Hedingham Witchcraft Case

The last witchcraft case in Essex, 1863

By Inspector Martyn Lockwood

Content Warning: Mention of hanging as punishment (no details), torture (no details) and assault by beating.

Throughout Europe during the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, many thousands of poor wretches were killed in the hunt for witches. In 1584 Pope Paul VIII issued an edict which made witchcraft a heresy and torture was used as a means of extracting ‘confessions’. In Essex alone, between 1560 and 1680, 74 persons were executed for witchcraft.

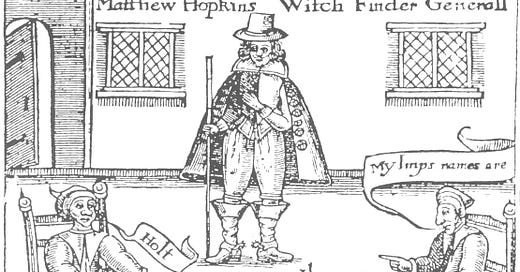

Matthew Hopkins, Witchfinder General

Matthew Hopkins was a little known lawyer practising in Manningtree in North Essex, when in 1644 he published a book ‘Discovery of Witches’. This was to lead to eight women being hanged in Manningtree for the crime and at Chelmsford, in 1645, some 19 women were condemned to the gallows.

Hopkins travelled throughout the Eastern Counties in his quest for witches and he was to become known as the “Witchfinder General”. There is some dispute as to how Hopkins met his end. Some accounts say he was himself hanged as a witch, while it is believed he died of consumption in Mistley in 1647.

One of the preferred methods of determining the guilt of a witch was known as ‘swimming’, where the victims, right thumb tied to left toe, were thrown into the water. If the poor soul sank they were declared innocent, whether they drowned or not, but if they floated then they were definitely a witch and met death at the stake. The ‘swimming’ was in accordance with the ancient belief that water, the element of baptism, would reject a witch.

The Last Witchcraft Case

By 1863 Queen Victoria had been on the throne some 26 years; the first underground railway was opened in London, whilst in America, the Civil War was two years old. The Battle of Gettysburg had been fought leaving some 40,000 dead in the cornfields and orchards of the small Pennsylvania township, and in rural Essex the village of Sible Hedingham was to become the scene of what is regarded by many as the last case of witchcraft to occur in this country.

By the nineteenth century attitudes had changed. Superstitious people still believed in witchcraft and those suspected of being witches were treated as outsiders and often avoided by other villagers. However in 1863, an elderly man died as a consequence of the shock of being ‘swum in water’ as a witch and two persons appeared in court in connection with his death.

The Victim

The facts of the case are simple. Sible Hedingham, a large scattered village of some 1800 inhabitants, consisted mainly of the agricultural labourer, or small tradesman class. The victim was an elderly man, by common consent a Frenchman, although it had to be admitted nothing was known of his nationality. He was deaf and dumb and at the time of his death was estimated to be 76 years of age. Nothing definite was known about his past, but it was rumoured that he had had his tongue cut out by the Chinese whilst fighting for the French. He had lived in a wretched mud hut on the outskirts of the village for several years and was known by everyone as Dummy and was a figure of curiosity. Always accompanied by several dogs, he wore several hats of different descriptions, all at the same time, and as many as three coats, depending on the weather at the time. Unable to speak, he communicated by means of signs and gesticulated in a vivacious, excitable and grotesque fashion. He gained a living by telling fortunes, in the main feeding on the superstitions of the local populace.

The Scene

The scene of the tragedy was The Swan Public House, which stood in the centre of the village and was a popular resort for the local population to while a way an evening. Nearby ran a shallow brook, no more than a few feet deep, in which the ‘swimming’ was to take place.

The Perpetrators

The other players in the tragedy were Emma Smith, 36 years of age, the wife of the beerhouse keeper at nearby Ridgewell. She was described as an emotional, excitable and highly strung woman and also very superstitious. Samuel Stammers, 28 years, a master carpenter by trade, who lived in the village, would also find himself standing alongside Smith in the dock at Essex Assizes, charged in connection with the death of Dummy.

The Crime

On the evening of the 3rd August Dummy was to be found in the tap room of The Swan. There were some 40 to 50 other people in the premises, including Smith and Stammers. Smith complained in a loud voice that she had been ill for some 9-10 months and that her illness was caused by Dummy, who had bewitched her. She begged him to return with her to her home at Ridgewell and remove the curse. So desperate was she that she offered him 3 gold sovereigns; but Dummy was having none of it, fearing that his life would be in danger if he went with her. She continued to plead with him, much to the amusement of the assembled audience, who sensing more fun, continued to encourage Smith. At closing time the action moved to outside The Swan, where Smith, still encouraged by the crowd which had now grown to some 80 people, continued to plead with Dummy.

Eventually, seeing she was getting nowhere, Smith struck him several times with a stick and dragged him towards the brook, where she pushed him in. Dummy tried to get out of the brook by the opposite side, but was prevented by Smith who had rushed round to cut off his exit. At this point Stammers appears to have joined in and the pair pushed the unfortunate man once more into the brook. Dummy managed to struggle out of the water and sat exhausted on the bank.

Smith and Stammers once again took hold of the old man and threw him back into the water where he struggled. The mood of the bystanders, who had until this time been encouraging the pair, assisting with a barrage of stones, now began to change as they became alarmed at what was going on. One shouted, “If someone does not take the old man out, he will die in a moment.” Stammers, perhaps coming to his senses, jumped into the brook and pulled the old man out onto the bank.

Dummy was assisted back to his home where he was left. The next day he was visited by a villager who found him in a terrible state, still wet and trembling violently and very badly bruised. He was in much pain and then screamed loudly when his wet clothes were taken from him. Superintendent Thomas Elsey, was informed and had Dummy removed to the Halstead Workhouse where he died on the 4th September, of pneumonia brought upon by the immersion and ill-treatment.

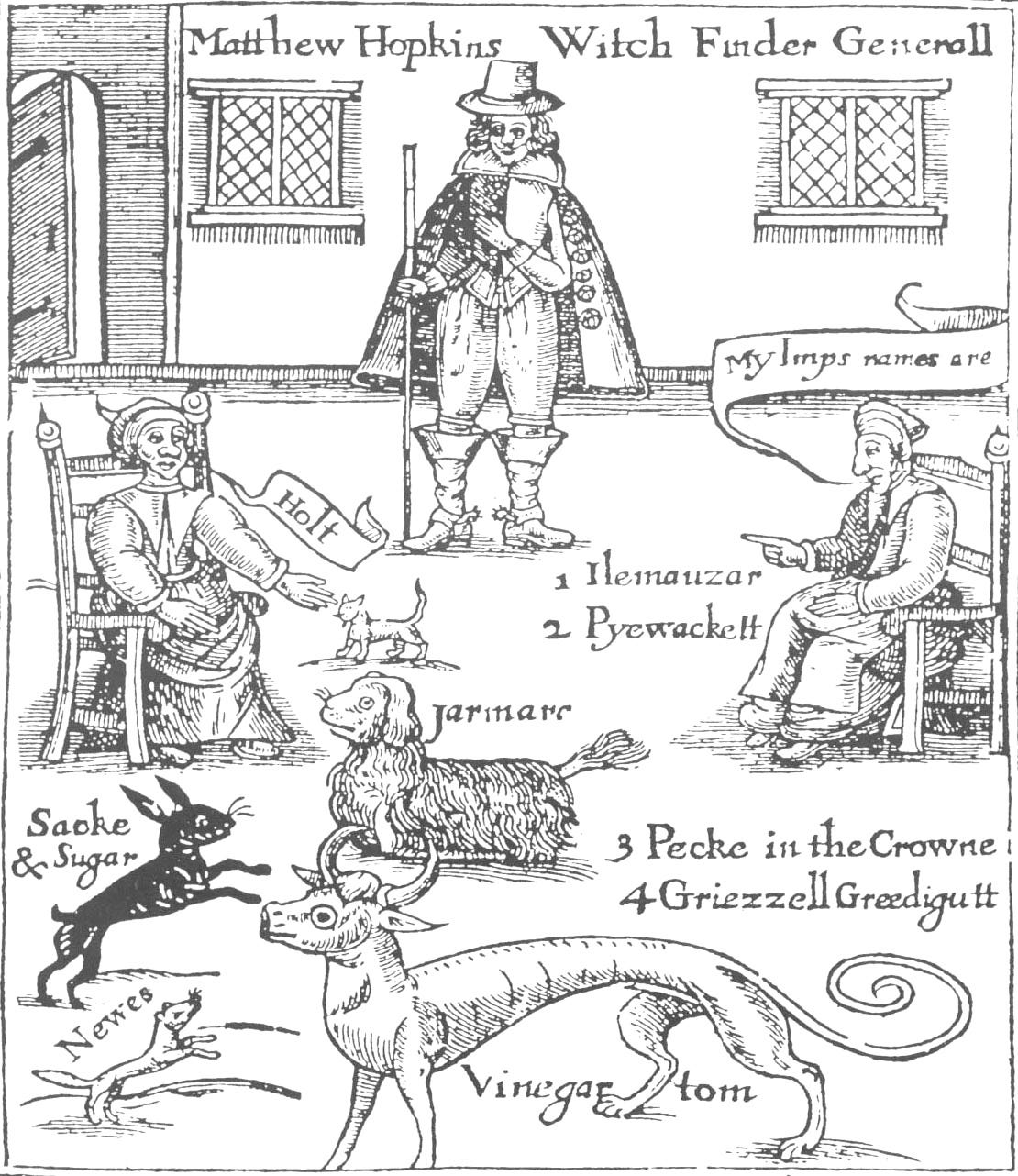

Death certificate transcription:

Registration District: Halstead

1863

Death in the sub-district of Halstead in the County of Essex.

No. 440, died 4th September 1863 at the Union Workhouse in Halstead.

Name: Dummy

Sex: Male

Age: Supposed to be about 76 years

Occupation: Unknown

Cause of death: Fever - 1 month, pneumonia - 3 weeks, certified

Signature, description and residence of informant: Thomas Twose, Master, Union Workhouse Halstead

When registered: 2nd November 1863

Signature of registrar: [illegible]

Investigation and Charges

The police under the direction of Superintendent Jeremiah Raison began an investigation into the events of the 3rd August and on the 25th September, Smith and Stammers were charged by Superintendent Elsey, before the magistrates at Castle Hedingham, with having “unlawfully assaulted an old Frenchman commonly called Dummy, thereby causing his death.” The case had attracted much interest and the small courtroom was packed. Witnesses to the events were reluctant to give evidence against Smith and Stammers, but several told the court the facts as are related above. Mr Sinclair, a surgeon to the Halstead workhouse, said that death was due to the treatment the old man had received. They were both committed to the next Assize court at Chelmsford.

The Trial

On March 8th 1864 the two accused stood next to each other in the dock. They pleaded Not Guilty. Smith told the court that the deceased had come to her house, had spat at her and told her that after a time she would become ill, and she was ill. She had called a doctor twice in one night and he could not cure her. Dummy, she told the court, made her ill and bewitched her. A telling witness against the two accused was a girl called Eva Henrietta Garrad, described as a ten year old child of precocious intelligence. Despite her tender age she unfolded in clear terms the events of the night to the court. The defence made strenuous efforts to discredit her, but her evidence was enough to place the guilt of Smith and Stammers beyond doubt. Much was made of the mental state of Smith and the fact that Stammers had pulled the old man out of the water. The judge, Sir William Erle, took these factors into account when he sentenced both defendants to 6 months hard labour.

Was Dummy a witch? Certainly he played on the superstitions of the local people. He was consulted by the local girls as a recognised authority on courtship and marriage; and when police searched his home they found numerous scraps of paper with various queries written on them. One such query read, “Her husband have left her many years, and she want to know whether he is dead or alive.” Even 130 years ago, in rural Essex the fear of witchcraft was a firmly held belief in the minds of country people.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are gratefully offered to Mr Adrian Corder-Birch