Messrs. J. Gripper Ltd, at 15 High Street, Chelmsford and 39 Market Hill, Maldon was a well-known firm of iron merchants and ironmongers. It was founded by Joseph Gripper and supplied a wide range of agricultural, light industrial and domestic goods. Herbert was the second son and took over the business when his father died in 1910. He was a wealthy man and had a new house, “Redcot”, built at 54 New London Road. He was involved in Chelmsford’s civic life as a councillor for South Ward between 1899 and 1908 and was instrumental in the building of the public baths at Waterloo Lane in 1906. He was also a keen golfer and helped establish the Chelmsford golf club and golf course.

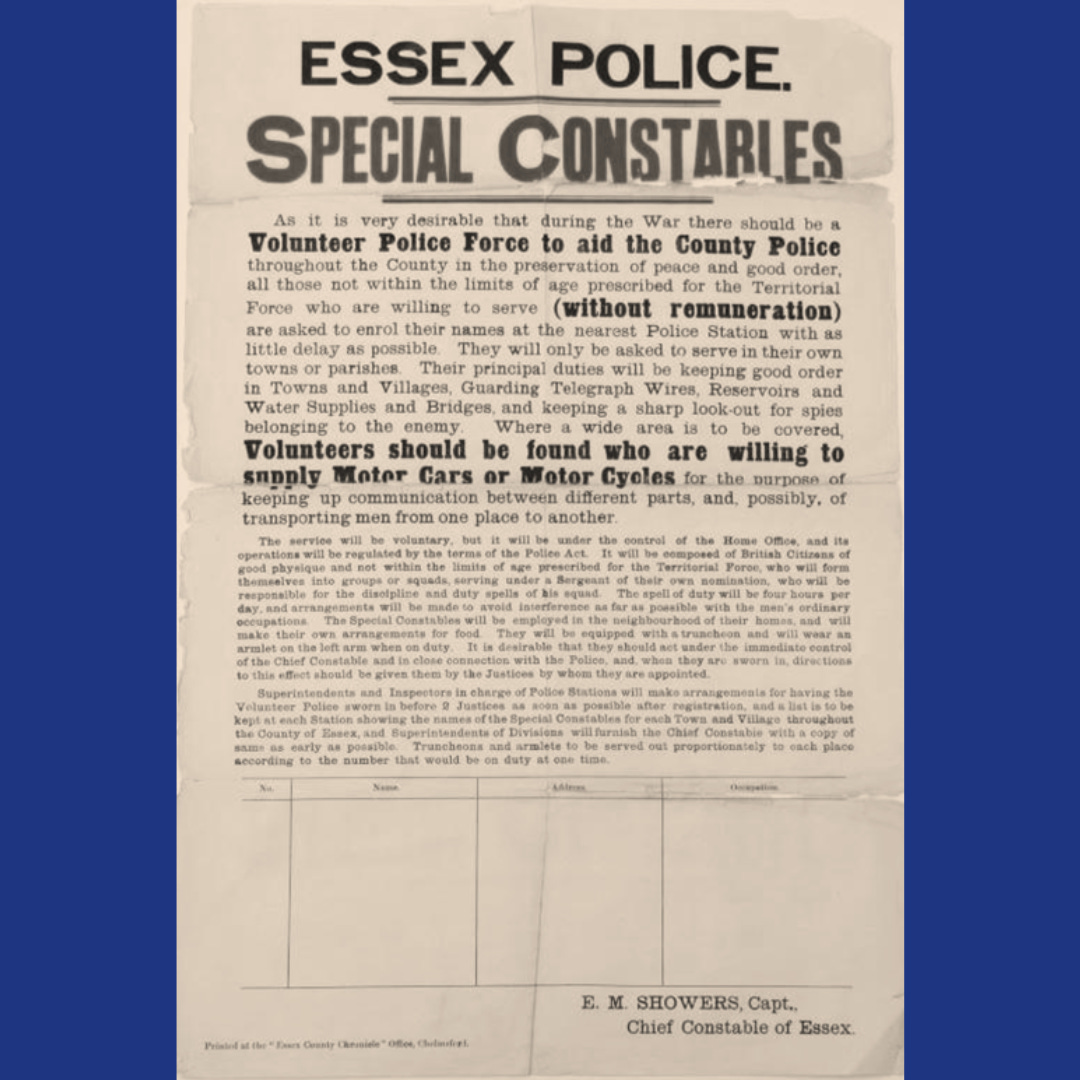

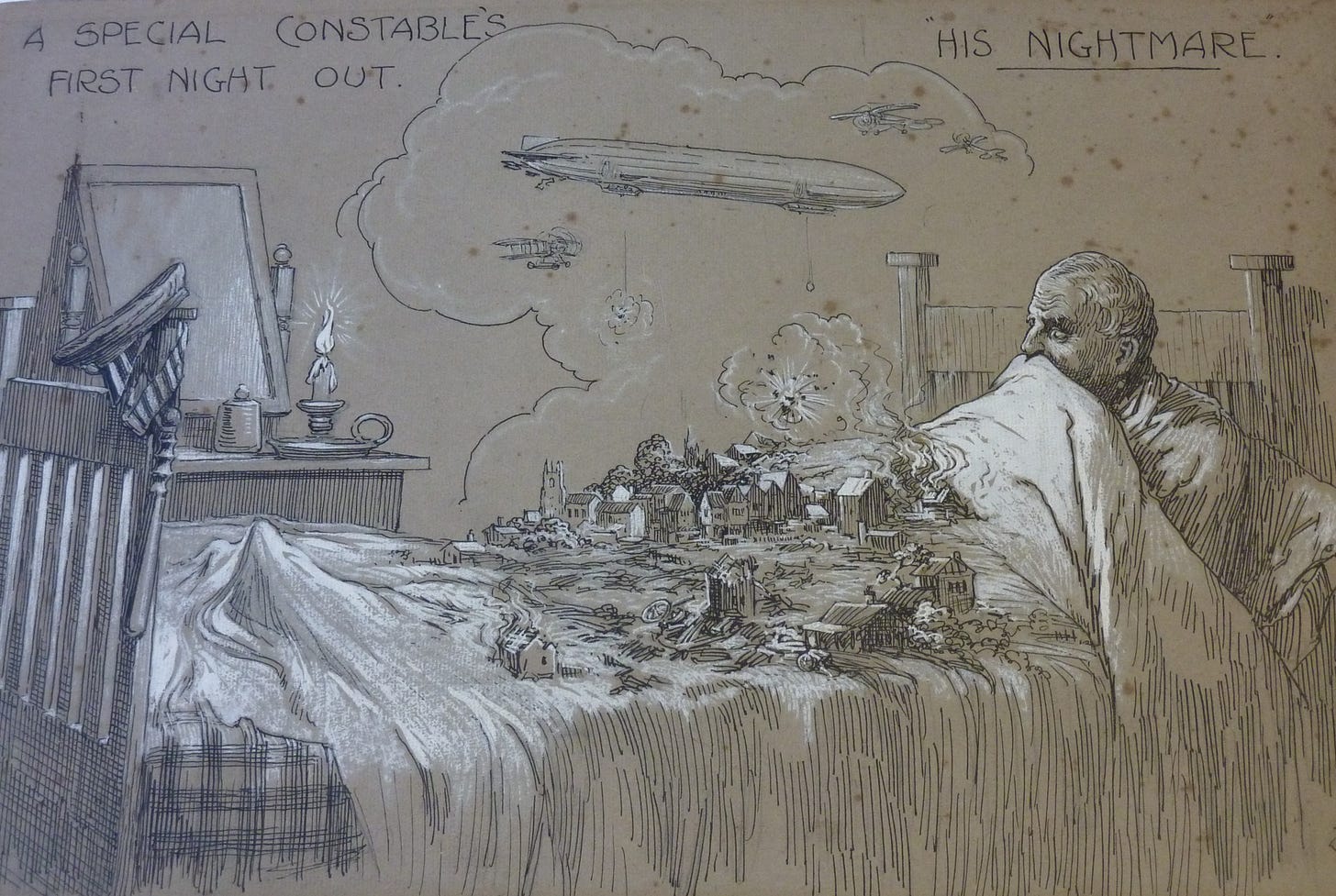

At the outbreak of the First World War Gripper was one of the first in Chelmsford to be sworn in as a Special Constable, on September 7th 1914. A week later he was issued with his warrant card, armlet and truncheon. The specials were men who were too old or unfit for military service and had a neighbourhood focus: Gripper was assigned to a post at the corner of New London Road and Writtle Road. He was in charge of a small team which patrolled the south of the borough as far as the Longstomps reservoir on Wood Street.

Gripper has left a valuable record of his service, now held at the Essex Record Office (D/Z 137/1). It comprises a handwritten log covering the period October 1914 to the disbandment of the Specials in 1919, and a collection of papers and orders received during this time.

Historically, Special Constables were recruited at times of civil disturbance and had specific powers to assist in the keeping of the peace, and for a limited period only. New legislation was required for these war-time specials, as the nature and duration of the threat was unclear. The new Specials had two roles: firstly, to assist the Chief Constable and the regular police, but secondly, and perhaps less well known, they were to assist the Lord Lieutenant and the Central Emergency Committee in the evacuation of the county in the event of invasion.

In late 1914 there was a serious and genuine fear that Essex would be the primary landing ground for a German assault. Gripper’s records show the evacuation plan for Chelmsford: residents of North Ward would assemble at Admiral’s Park, those of South Ward at the Recreation Ground (now Central Park), and Springfield residents would gather opposite the gaol at Arbour Lane. Gripper and his colleagues would act as guides and lead parties through the back roads by way of Rainsford Road, Chignal Road, out to Chignal St James, Mashbury,

Good Easter and to Dunmow, and then on to Welwyn in Hertfordshire. This was not a temporary scare: the evacuation plans were revised throughout the war, with final updates as late as the summer of 1918.

Most of Gripper’s work was trivial. In the early days he notes hearing owls and watching shooting stars out at the reservoir. He also covered a large area on patrol: in January 1915 his beat ranged over Springfield Church, the old White Hart, Hill Road and Navigation Road. In April he was patrolling the area between Baddow Road, Writtle Road, Waterhouse Lane and Rainsford Road.

At around this time the first Zeppelin raids started. There was no formal public air raid warning system to begin with, but on seeing or, more commonly, hearing an enemy aircraft the military authorities would issue a preliminary warning to the local police, and it was down to the borough Chief Superintendent to issue the order to “Take Air Raid Action”, usually when the Zeppelin was believed to be overhead. This was telephoned to the Special Constables’ patrol posts, and they would then instruct the population to extinguish or obscure all lights. In May 1915 Gripper recorded that Zeppelins had been seen over Mersea, and the following month he noted that the airships had been observed over Bradwell and Sheerness and that one passed over Galleywood “just as we were turning in”. On Tuesday August 17th 1915 his logbook records that a “Zepp dropped bomb on [7] Glebe Road and another in Admiral’s Park but little damage”.

On April 25th, 1916 Gripper was called out when a Zeppelin “came right over and [we] had an excellent view at 11.15 [pm] of 4 searchlights on her. Gun fire but she came right over again apparently wounded”.

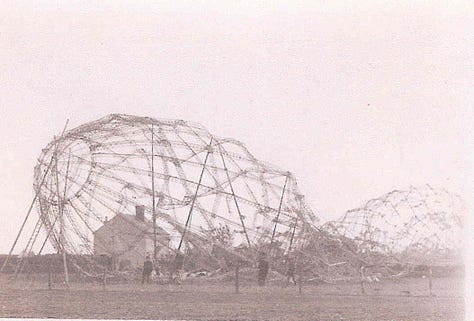

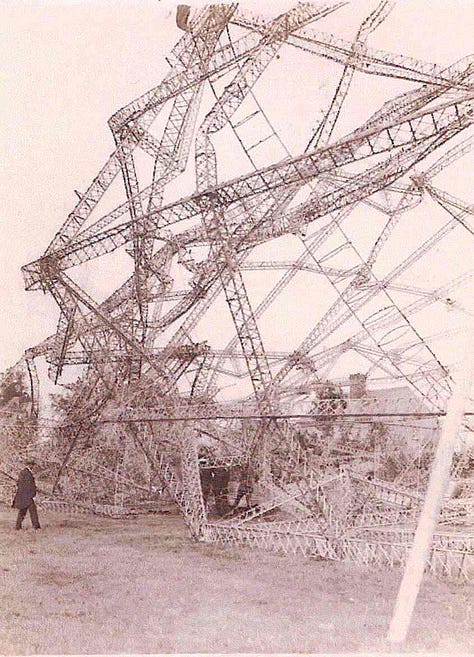

This spectacle was surpassed on Saturday September 23rd: “8.30 preliminary [warning]. 9.35 Take action. 12.30 Zep passes SW to NE. Guns fired and bombs dropped. At 1.20 SW saw a Zep on fire which came down at Billericay. Great flame of light. Wonderful sight. At 1.30 another red flame due east. Zep went down at Great Wigborough.”

The air raids became increasingly severe later in the war. Although the Zeppelin threat diminished, in 1917 the Germans switched to daylight raids using Gotha bombers. For some reason Chelmsford was never the focus of an attack, but the distinctive features of the Essex coastline helped the raiders navigate their way to London and to the industrial towns of the Midlands, so the town was regularly overflown. On December 18th, 1917 there was an alarm at 7.05 pm. “Heavy guns firing for the past half hour. Aircraft went over at 7.20. More again 7.30 East to West. Searchlight on one plane. Star shells and heavy firing + shells overhead. All clear at 10.05. At 9.30 saw one brought down direct SE about 10 miles.”

On January 28th , 1918 Gripper recorded another raid: “At 8.15 firing at aircraft which came about 5 miles to the south. 8.20 a bad shell fell about 400 yards to south of Oaklands. 9pm another lot passed nearly over. Heavy and continuous firing up to 11.30 SW and W to nearly NW. Firing again at times up to 1am”.

An intriguing feature of Gripper’s notebooks is that the entries were clearly written at the time, and not at some later date; and yet he is able to provide details about raids that never appeared in the newspapers. For example, in the December 18th raid mentioned above, Gripper adds that there were 16 to 20 aircraft in six groups which went on to bomb London, leaving ten killed and 70 wounded. He has details of raids on Harwich and the north coast which suggests that the Special Constables were in communication with their colleagues over a wide area and able to share news and reports immediately.

The night of Tuesday June 27th, 1916, was very quiet. While on patrol Gripper heard a distant rumbling sound, and wrote in his diary: “Guns in Flanders seen and felt”. This was the enormous artillery barrage that preceded the Battle of the Somme.

Gripper also carried out routine police duties. In November 1915 there was a crackdown on bicycles with no lights, and his group caught 20 offenders who were summoned and fined. In May 1916 he was a witness in the prosecution of Alec Auger, of Little Waltham, who was caught driving along New London Road at a speed Gripper estimated as “considerably over 40 miles per hour”. The young man was given a heavy fine of £5 (about £350 today).

One of Gripper’s neighbours on New London Road was a local magistrate, Mr F. H. Crittall, J.P., who lived in what is now Southborough House. On the night of March 31st 1916 the air raid action warning was given to Gripper by Superintendent Mules, the chief of police in Chelmsford. Gripper noticed lights from upstairs and downstairs windows in Mr. Crittall’s house and ordered that they be extinguished. The magistrate refused and when the Special Constable checked again a few minutes later and saw that the lights were still on he had no choice but to report him. Crittall suffered the embarrassment of appearing in his own court later that month and was found guilty. It was then noticed that this was his second conviction for this offence, so his colleagues fined him £10 (about £700). The bench also ordered costs of 5s (about £17.50) to be paid to Gripper.

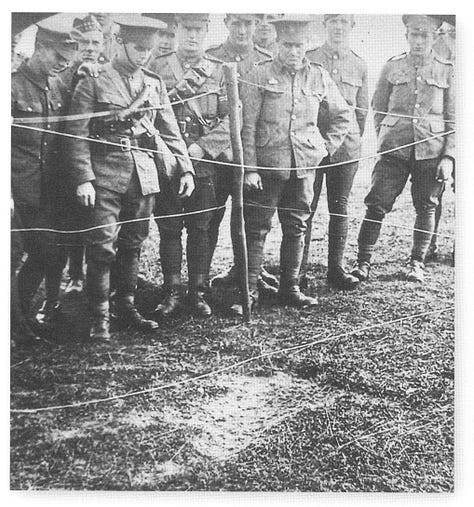

On Friday August 6th, 1915 Gripper had an early start, parading at 7.30 am and taking up a position at the end of Elm Road to direct the traffic coming out of Chelmsford to Hylands House, where Lord Kitchener was reviewing the troops of the South Midland Division. He had crowd control duties when General French reviewed the Volunteer Corps on Sunday October 22nd 1916 and again when French returned on January 27th, 1918. And in a little-known footnote to history, he paraded for the American General Pershing on a visit to Widford Camp on June 12th, 1917.

The last air raid action at Chelmsford recorded by Gripper was on Sunday May 19th 1918. Although the patrols continued through the summer, life was much quieter. The Specials joined the Red Cross parade through the town on Sunday 6th October 1918 and the following month the war ended. Gripper’s last duty as a Special Constable was to act as a guard for the ballot box at the St. John’s Church voting station for the General Election on December 14th, 1918.

Herbert Gripper kept some statistics of his service. During the course of the war he carried out 152 patrols, attended 54 drill nights and walked 740 miles. He reported lights at 752 houses. The Specials were officially disbanded on July 14th, 1919. Gripper survived to receive his Long Service medal in 1921 but died in September 1923 at the age of 65. His notebook ends with a postscript:

Now it’s all over

We do not want medals or OBEs

We thank the Almighty while standing at ease

And having received our final dismiss

Just go back to our home and family – bliss.Special Constable 413

Herbert Gripper summed up his experience as a Special in a poem:

The New Year Bells are ringing

A note of peace to all

And soon the poor red Specials

Will have their final callNo more the Hooters Siren

Will sound its shrilling screams

No more the Generals whistle

Will rouse us from our dreamsNo more in icy blackness

The Reservoir to guard

Or tramping round the viaduct

And the smelling railway yardNo more in midnight watched

We wait the Zeppelin’s hum

Or watch the bursting shrapnel

As the raiding Gothas comeNo more our worthy Sergeant

Will send us out at night

To watch and ward the Borough

And see the lights too brightWe may not get a medal

We cannot win VC

We have only done our duty

Without reward or fee

Original from the Essex Record Office (D/Z 137/1).