By Hannah Wilson, Curator

World War I had a huge impact on policing in Essex - officer numbers reduced by a third as officers joined the Armed Forces, and thousands of Special Constables were recruited to boost numbers. On top of regular policing duties officers had many new responsibilities related to the War, from guarding important sites to dealing with a German zeppelin crash. By the end of the War, 33 officers had been killed on active service - 22 from Essex County Constabulary and 11 between the Colchester Borough and Southend-on-Sea Constabulary Forces.

The Outbreak of War

The outbreak of war in 1914 marked the start of one of the most challenging times in Essex policing history. At the time, policing wasn’t a protected profession, meaning officers were free to join the Armed Forces as they wished - lessons were learned and this was changed in World War II so officers needed permission. 150 out of 450 officers left to join the Forces, leaving just 300 officers across the county. War and the threat of invasion created many new responsibilities, and it became obvious more man power was needed.

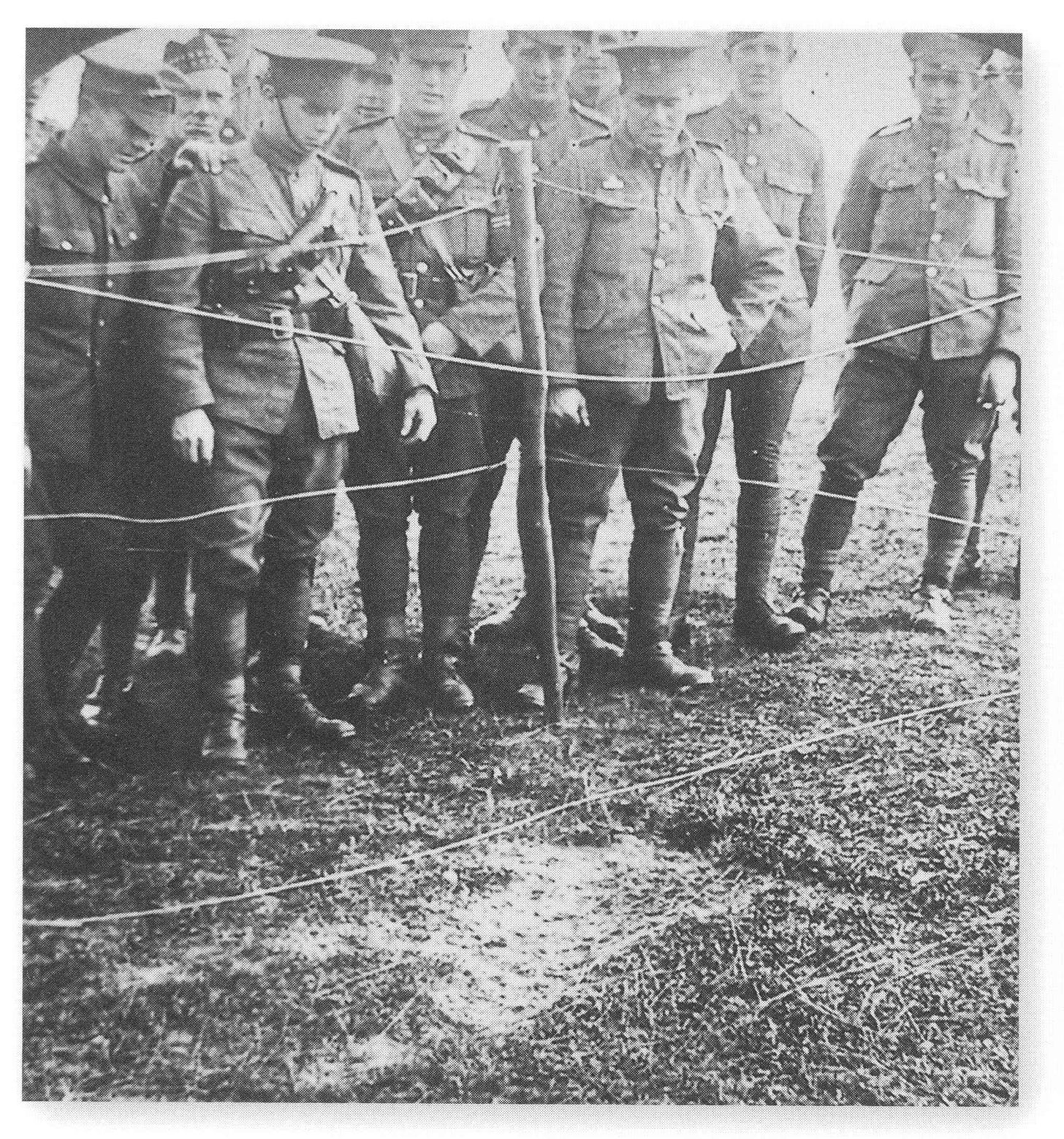

Special Constables

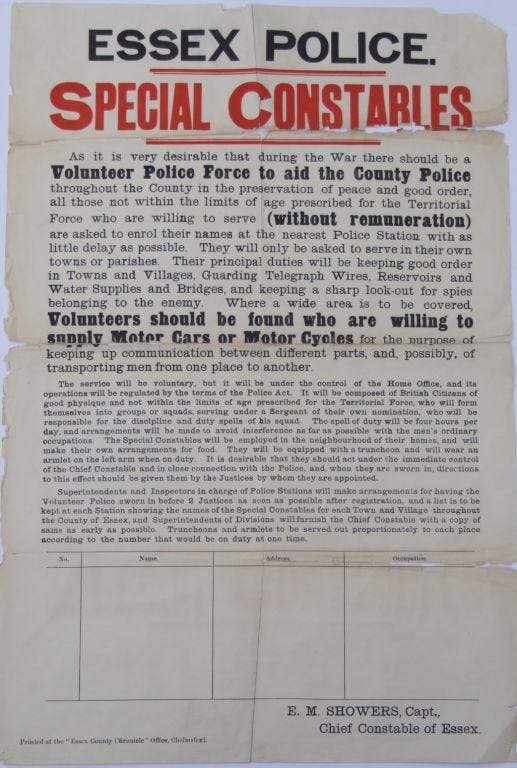

To address the increased demand for man power the Home Office introduced a team of 6000 volunteers, known as Special Constables, or Specials for short. Legislation had been in place for quite some time before the advent of War, and Special Constables had policed local strikes and industrial action, but this is the first mass recruitment of Specials as we know them in the County Force.

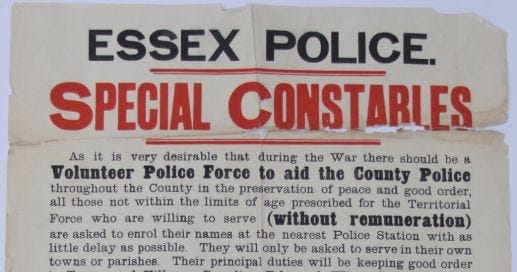

Transcript of recruitment poster:

“Essex Police Special Constables

As it is very desirable that during the War there should be a Volunteer Police Force to aid the County Police throughout the County in the preservation of peace and good order, all those not within the limits of age prescribed for the Territorial Force who are willing to serve (without remuneration) are asked to enrol their names at the nearest Police Station with as little delay as possible. They will only be asked to serve in their own towns or parishes. Their principle duties will be keeping good order in Towns and Villages, Guarding Telegraph Wires, Reservoirs and Water Supplies and Bridges, and keeping a sharp look-out for spies belonging to the enemy. Where a wide area is to be covered volunteers should be found who are willing to supply Motor Cars or Motor Cycles for the purpose of keeping up communication between different parts, and, possibly, of transporting men from one place to another.

The service will be voluntary, but it will be under the control of the Home Office, and its operations will be regulated by the terms of the Police Act. It will be composed of British Citizens of good physique and not within the limits of age prescribed for the Territorial Force, who will form themselves into groups or squads, serving under a Sergeant of their own nomination, who will be responsible for the discipline and duty spells of his squad. The spell of duty will be four hours per day, and arrangements will be made to avoid interference as far as possible with the men’s ordinary occupations. The Special Constables will be employed in the neighbourhood of their homes, and will make their own arrangements for food. They will be equipped with a truncheon and will wear an armlet on the left arm when on duty. It is desirable that they should act under the immediate control of the Chief Constable and in close connection with the Police, and, when they are sworn in, directions to this effect should be given them by the Justices by whom they are appointed.

Superintendents and Inspectors in charge of Police Stations will make arrangements for having the Volunteer Police sworn in before 2 Justices as soon as possible after registration, and a list is to be kept at each Station showing the names of the Special Constables for each Town and Village throughout the County of Essex, and Superintendents of Divisions will furnish the Chief Constable with a copy of same as early as possible. Truncheons and armlets to be served out proportionally to each place according to the number that would be on duty at one time.

E. M. Showers, Capt., Chief Constable of Essex”

Author Alan Cook says

“What made this time fundamentally different was the longevity and scale of the situation. Such was the contribution of special constables during the war a decision was made in 1919 to institute a 91 medal for faithful service in the special constabulary. When Essex faced the tumults and disturbances of the Swing riots in late 1830 the county created what were referred to as preventative “constabulary forces”. These were short lived and cannot be described as being a “special constabulary” which is what started to take form in the First World War. Once again, the legislation concerning the appointment of specials had to be reviewed to ensure it fitted a wartime context. When the special constabulary medals were presented to members of the Essex Special Constabulary in 1921 it was reported that 10,000 men had served as special constables during the war. This impressive total shows a level of commitment and desire to perform patriotic duty on a scale which is difficult to appreciate. When the war started it was assumed it would be over within a short period and the volunteer specials were told they would only perform duties as and when required. The reality was to be so very different and with Essex being such a strategically important county in terms of its location and coastal access the specials played an important role in the defence of the county.”

Alan Cook, Broken Heads and Shattered Truncheons

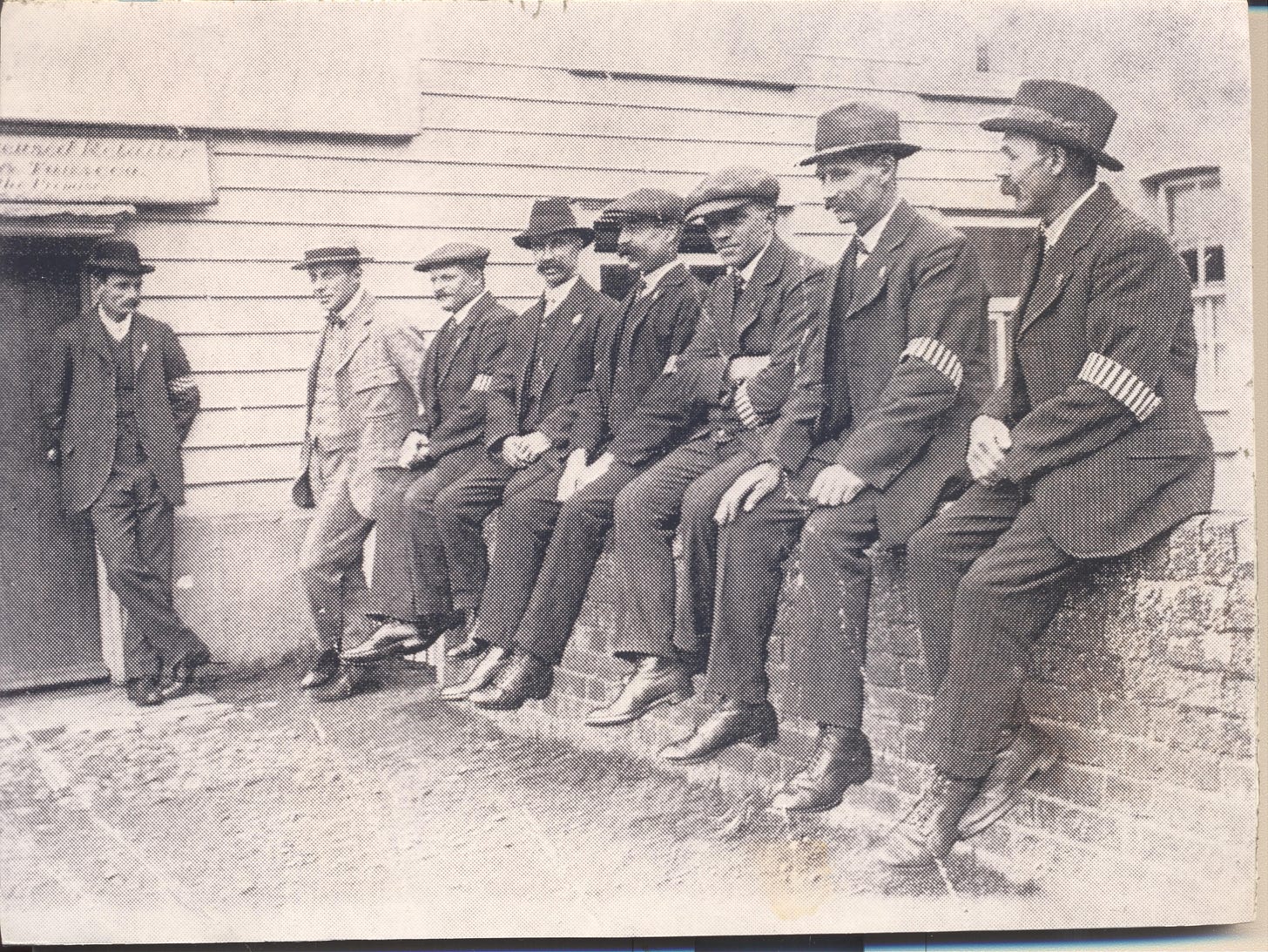

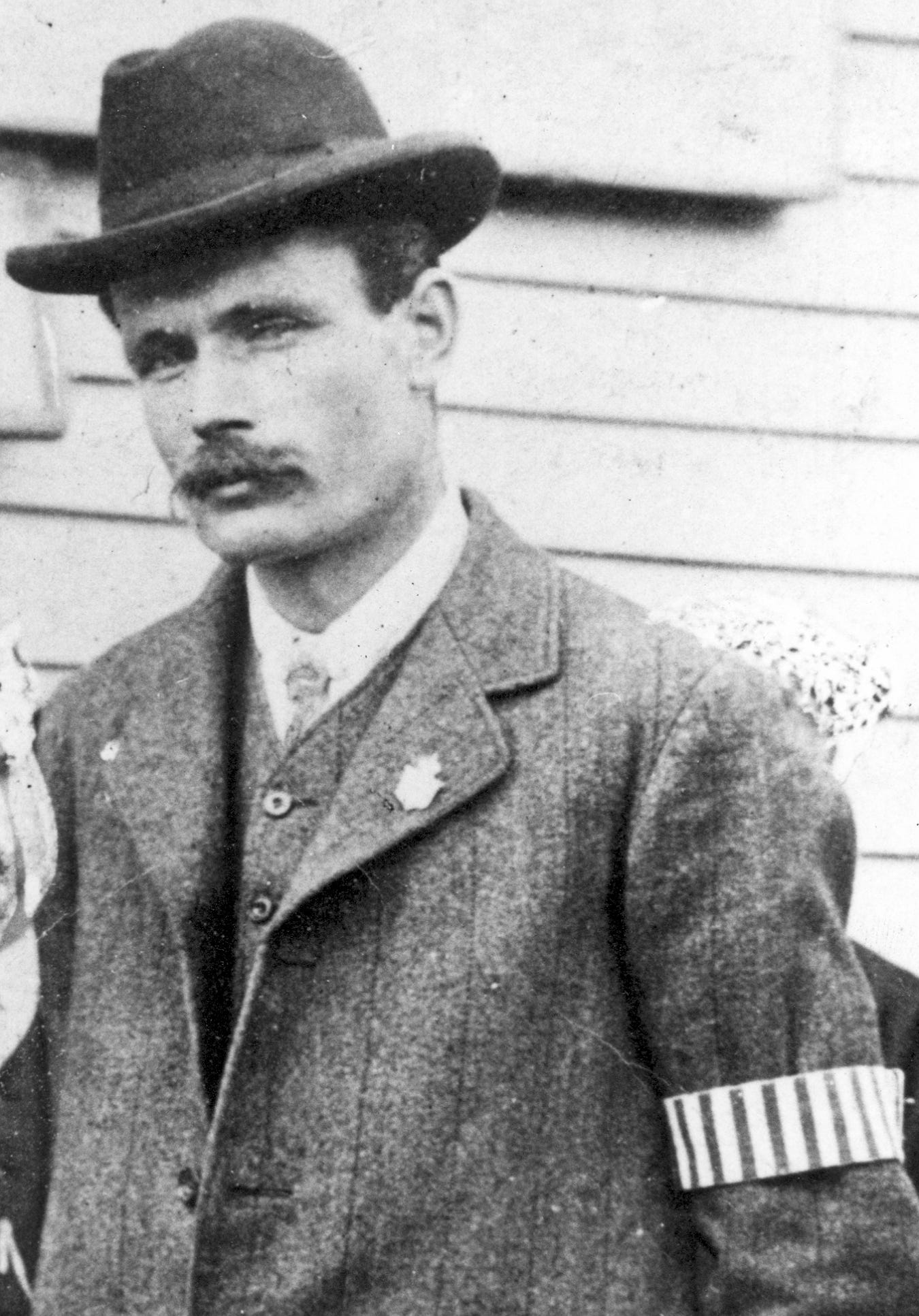

Essex always had a minimum of 500 Special Constables, which was effectively a second full-strength police force with its own rank structure. Uniform was not always available, but Special Constables were issued with a warrant card, truncheon and armband. Their duties included the guarding of vulnerable points, such as bridges and railways, enforcing blackout regulations and dealing with forged ration coupons. Some were employed full time and were paid, but most did one or two 4-hour sessions a week, unpaid. A similar system is used today; all modern Specials are volunteers and meet a minimum commitment of 16 hours each month. They receive the same training as 'regulars' (full time paid officers).

Placard reads:

“Duty Armbands, c.1914

Armbands were worn by the first specials to identify them as they did not wear a uniform. The horizontal striped armband is from the Colchester Borough Special Police. The embroidered star may have been a badge of rank.”

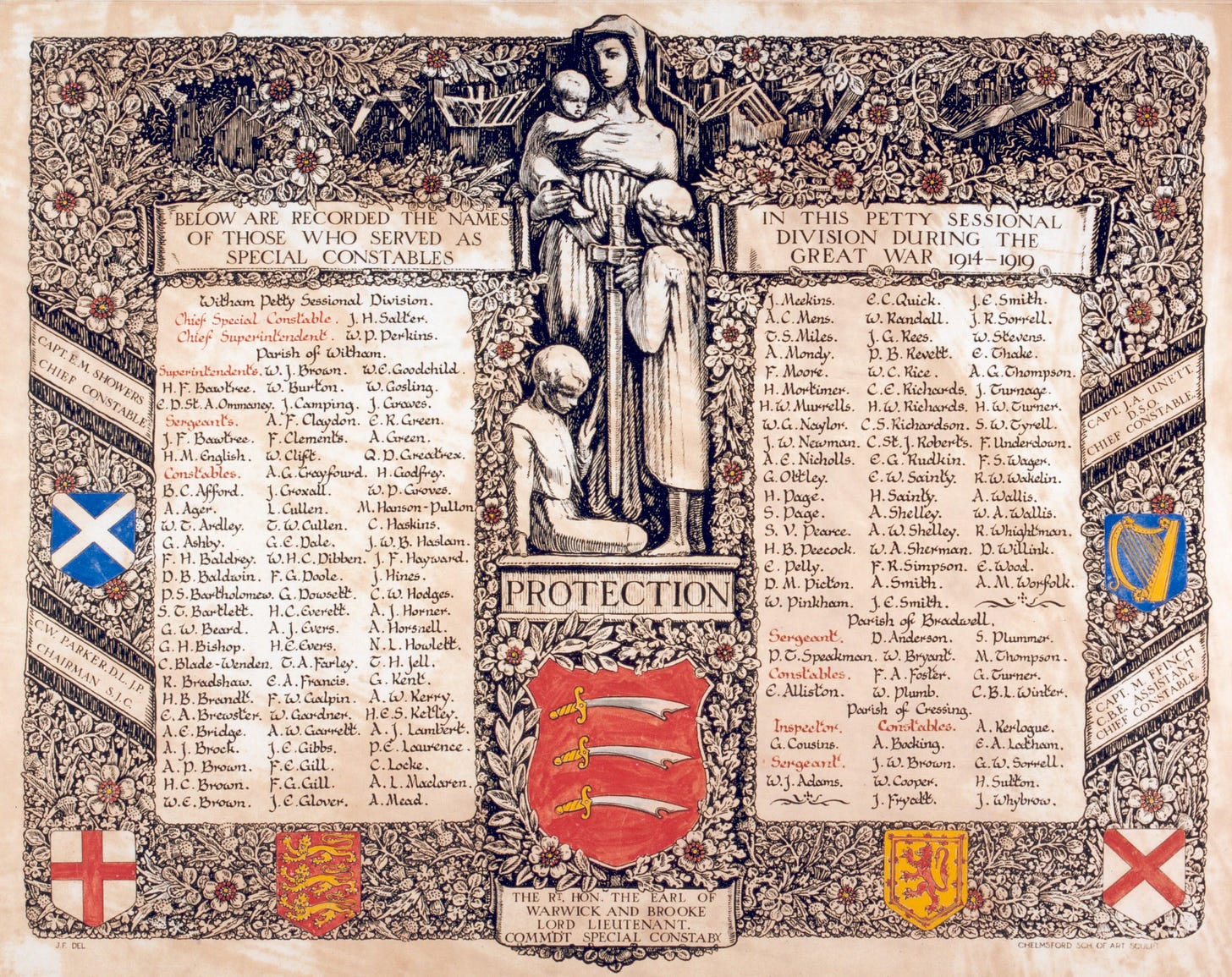

To recognise the service of Specials across the County a series of scrolls were produced listing the names of all those who served. The below example is for Witham Parish.

The new volunteer force was disbanded after World War I. However, Captain Showers recognised the benefit of having a reserve force, so kept them together by creating the Essex Police Special Constabulary Reserve. When war broke out for the second time two decades later procedures and protocol were already in place for recruiting more volunteers.

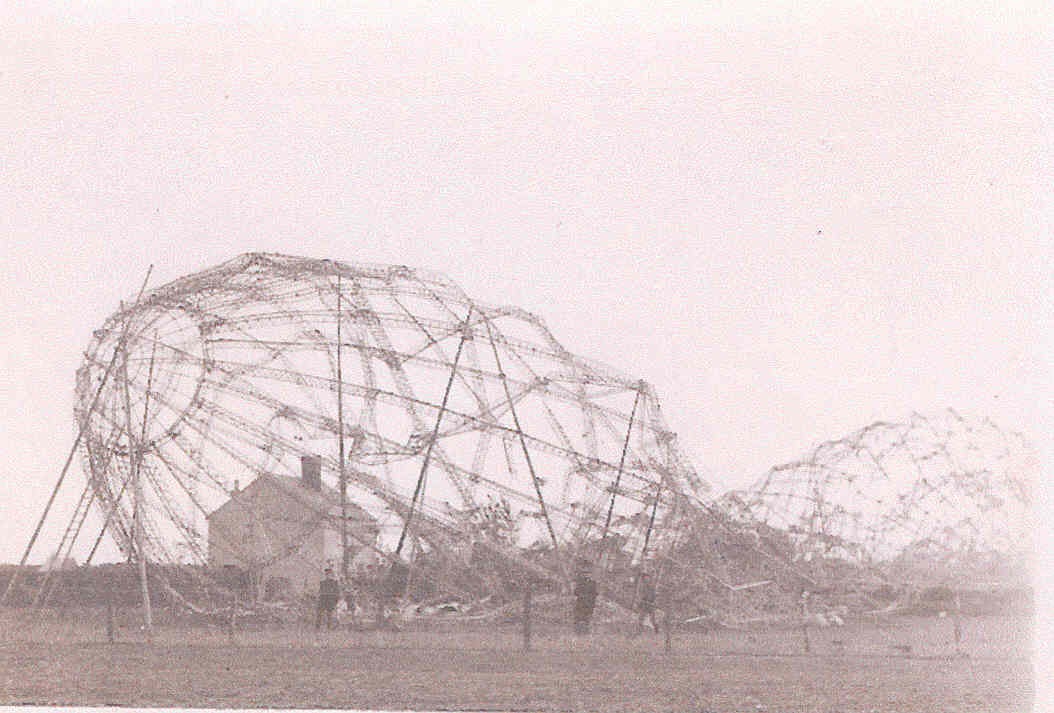

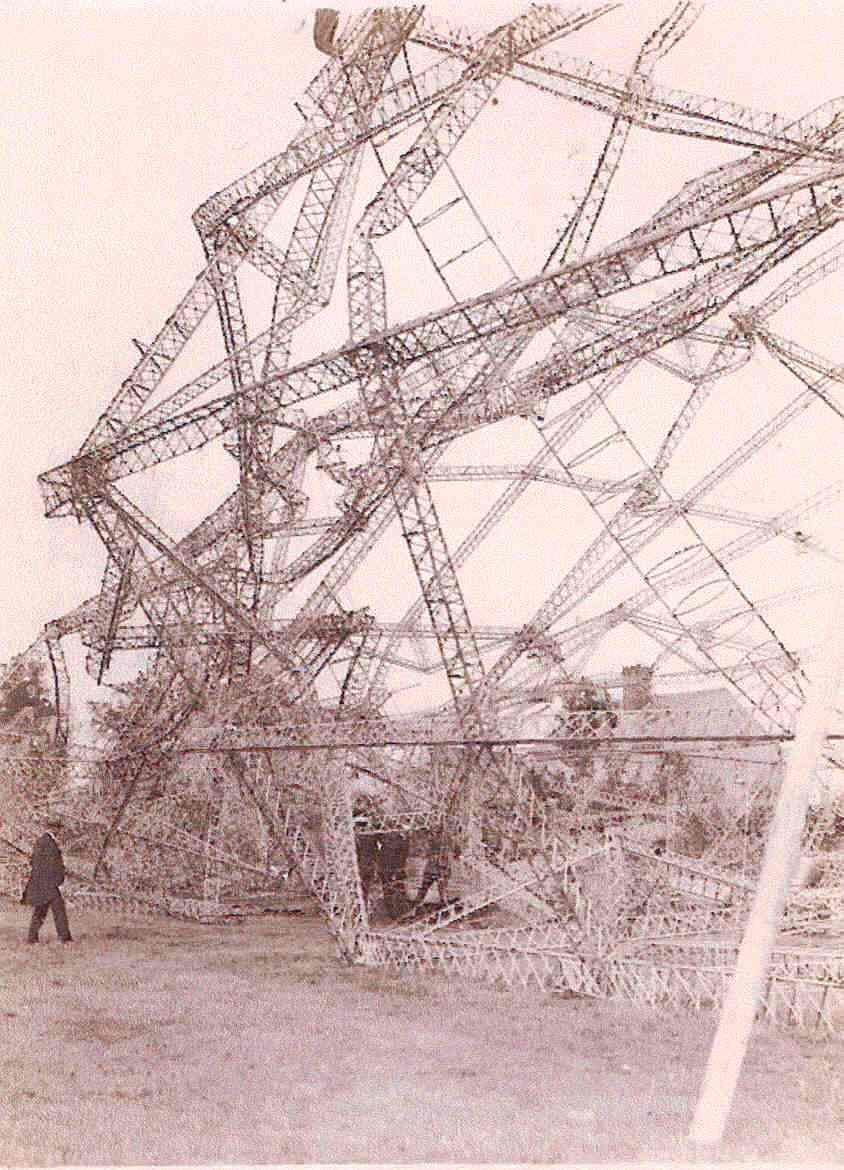

Zeppelin L33

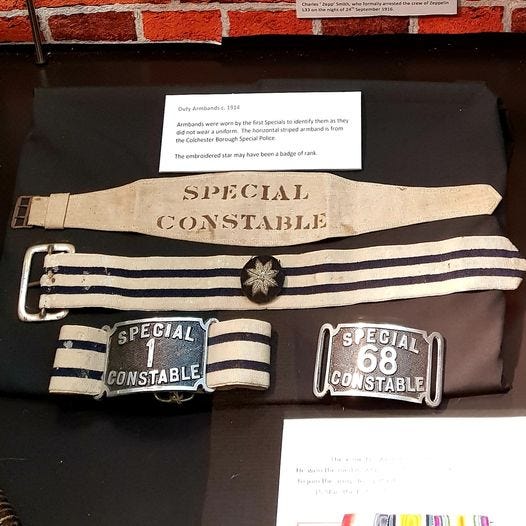

On the night of 24th February 1916, a zeppelin was shot down and crashed in Little Wigborough. The pilot, Captain Bocker, decided to set fire to the ship and march his crew to Colchester to surrender to the military. Special Constable Edgar Nicholas was on patrol on his bicycle when he saw the fire and then the crew. When Bocker asked him how far it was to Colchester, he recognised the man’s German accent and followed the crew. This is his account of the incident:

“The men proceeded towards Peldon Village; I followed walking with the rear men, one of whom spoke in broken english. I asked this man if he was hit by gunfire; he answered; ‘Zeppelin explode, we crew prisoners of war.’ Later he remarked ‘what people think of war?’ I replied, ‘I hardly know'.’ He said, ‘Did I think [the war] nearly over?’ I replied, ‘It’s over for you anyway.’ He answered, ‘Good, good,’ offering me his hand to shake which I did. After this he gave me his lifesaving vest and a screwhammer which later he informed me in good english was his revolver; with regard to the vest, he said ‘Schwim, schwim’ extending his arms in a swimming fashion and added, ‘Souvenir. Commander speak english, I learn english at school.’

Opposite Peldon Hall Lower Barn Gate I was joined by Special Constable Taylor and Sergeant Edwards (on leave staying in Wigborough). We all continued towards Peldon Post Office where we were met by PC Smith, stationed at Peldon, who took charge of the men.”

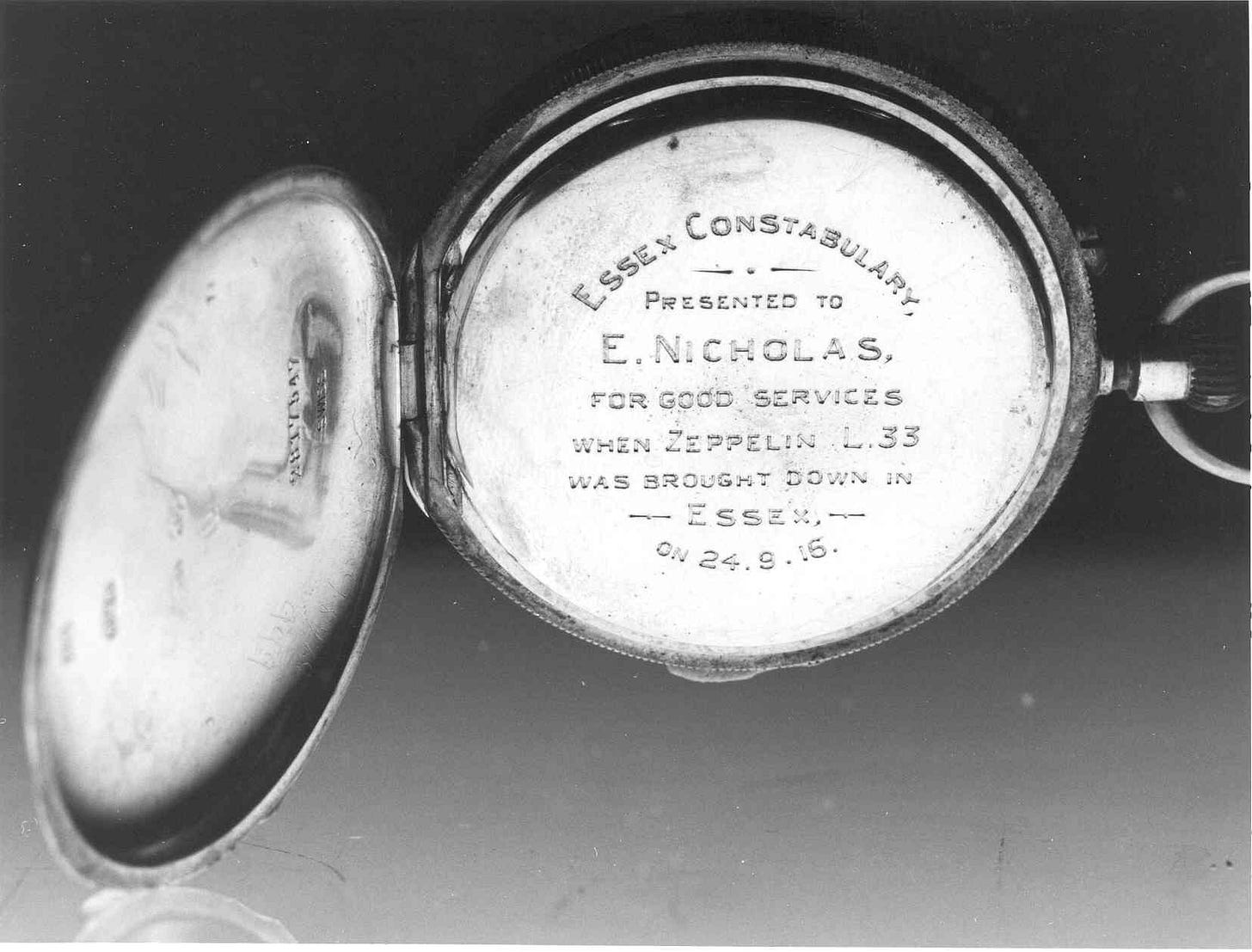

Edgar Nicholas received a pocket watch in recognition of his service during the incident. It was engraved with

“Essex Constabulary, presented to E. Nicholas, for good services when zeppelin L33 was brought down in Essex on 24.9.16”

PC Smith marched the men to West Mersea to hand them over to the military. For his actions, he was promoted in the field to sergeant and was awarded the Merit Star. He was known by the nickname ‘Zepp’ Smith until he died in 1977.

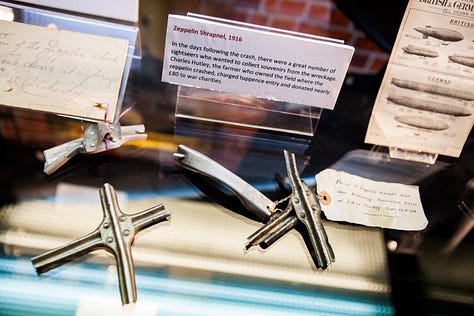

In the days following the crash, there were a great number of sightseers who wanted to collect souvenirs from the wreckage. The farmer who owned the field where the Zeppelin crashed charged tuppence a head entry and ended up collecting nearly £80, which he donated to war charities. Parts of the wreckage were smelted down and turned into ashtrays and commemorative pins. Proceeds from these sales also went to war charities.

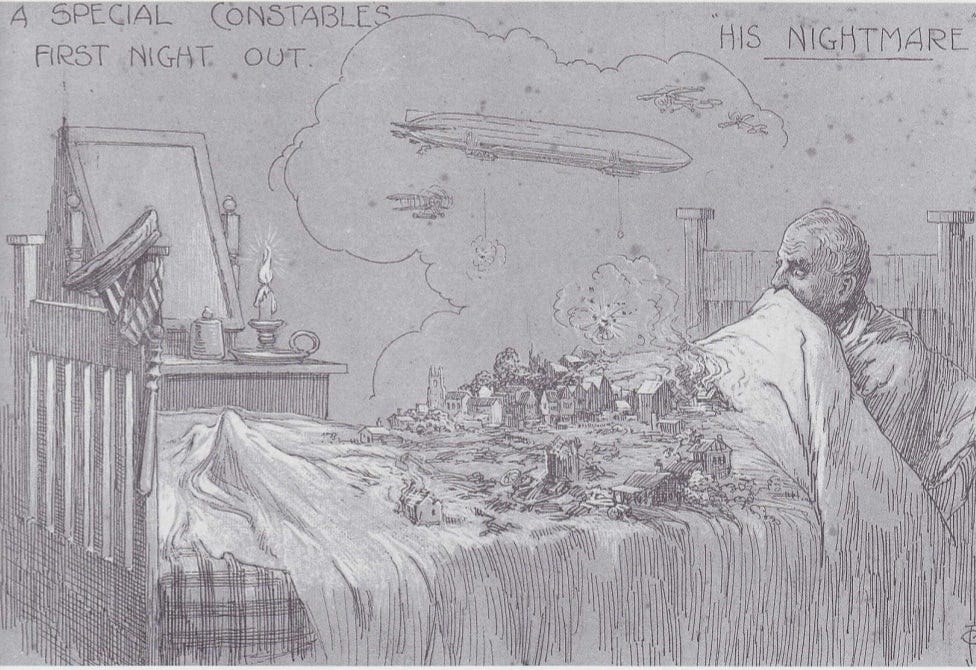

A Special Constable’s Nightmare

World War I had been a complex time for both regular Constables and Specials, with lots of changes; there were many new duties and new crimes on top of traditional patrols. Civilians, Armed Forces personnel and police personnel alike experienced war-related trauma. The below cartoon, part of a set of three in the museum collection, shows the psychological impact of the war on one Special Constable. Titled ‘A Special Constable’s First Night Out: His Nightmare’, it portrays an English town smouldering and damaged after a zeppelin bomb attack.

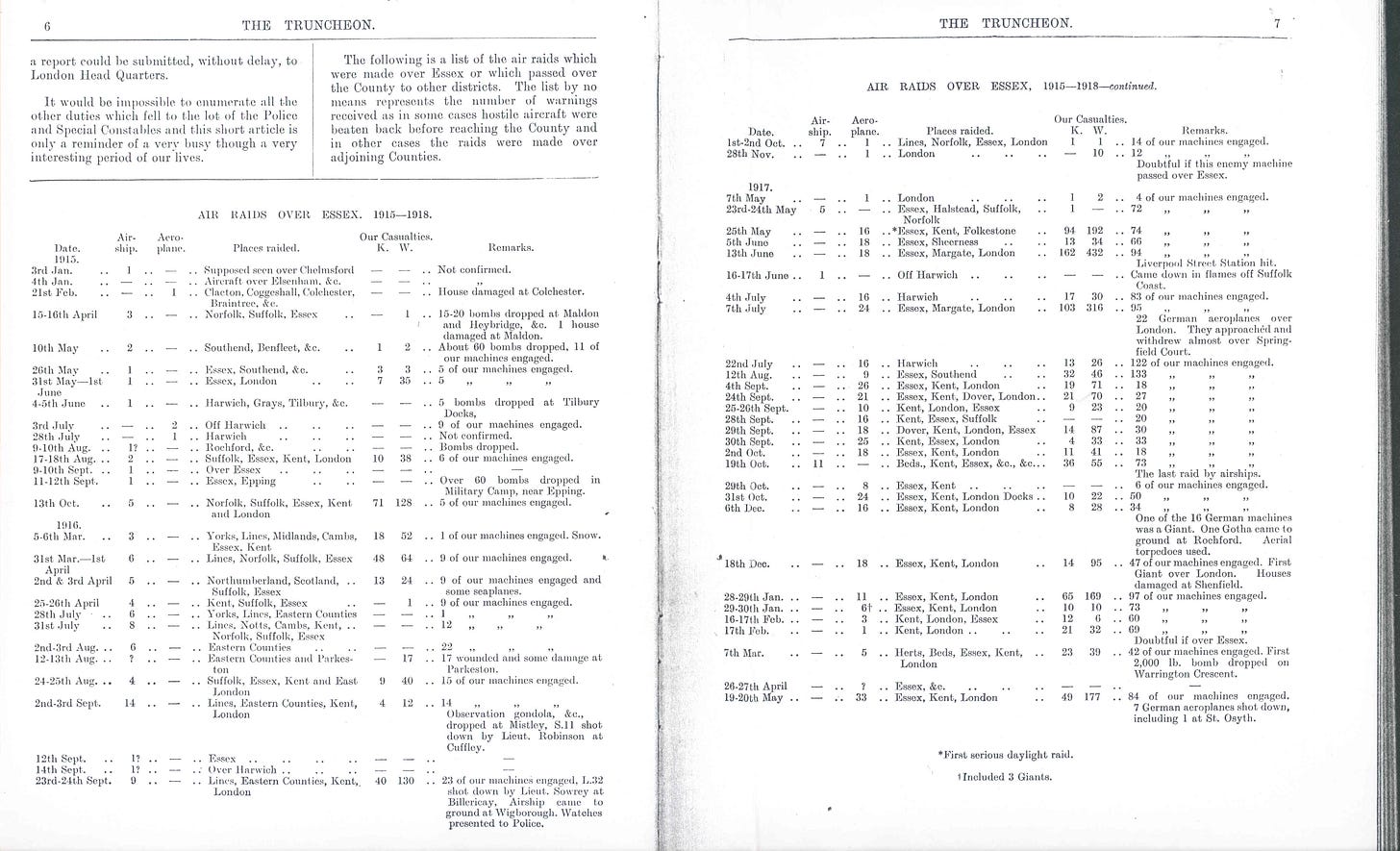

Air Raids Over Essex, 1915-1918

The below except from The Truncheon (1931), the Force Newspaper, summarises the air raids over Essex throughout most of World War I. Click on the image to zoom.

By the end of the war 59 air raids had killed 987 people and wounded 2594. The biggest casualties came on the 13th of June 1917, when 18 aeroplanes killed 162 and wounded 432 in a single attack across Essex, Margate and London. 94 British machines were engaged in defending against them, and Liverpool Station was hit.

Rare Object: Fire Grenade

This blue bottle dating from World War I, known as a fire grenade, is actually an early fire extinguisher. The bottle would be thrown into the seat of a fire - the glass would smash and the heat of the fire would turn the liquid carbon tetrachloride into carbon dioxide, which would suffocate the flames. We don’t have any information about its efficacy, nor the maximum size of the fire it would extinguish in one go, but we assume it would suit smaller fires. Users may also be restricted by the environment, as prolonged exposure to carbon dioxide is toxic and potentially deadly. Fire grenades are rare objects as once used they are broken beyond repair.

Essex Police Memorial Trust

The Essex Police Memorial Trust are dedicated to the commemoration of all those who died in World War I, World War II and those who died on duty. They take care of police memorials and plaques across the county and have compiled a roll of honour online.

Further Reading

Broken Heads and Shattered Truncheons: The Essex Special Constables 1800-1913, Cook, Alan (2022)

History Notebook 7 - Somewhere Over Essex: The Zeppelin Raids on Essex, available as a pdf download here.

History Notebook 59 - We Will Remember The Police Officers of Essex Killed in the Great War, available as a pdf download here.

Special Constable 413 Herbert Gripper: A Unique Look at World War I